Download PDF

CE Quiz

Abstract

Encephalopathy, a multifaceted condition marked by altered brain function, poses significant challenges in diagnosis, documentation, and coding within clinical settings. It occurs secondary to an underlying condition and requires specific diagnostic clarity to distinguish its types, such as hepatic, hypertensive, or metabolic encephalopathy, each presenting with unique clinical indicators. The lack of official coding guidelines for encephalopathy exacerbates these challenges, leading to frequent claim denials. Consistent and clear communication among healthcare providers, coders, and clinical documentation specialists is essential for validating diagnoses and accurately representing a patient’s condition. Via a review of 26 articles and forums, the authors synthesize the complexities of encephalopathy diagnosis and documentation, exploring how varied etiologies impact coding accuracy and reimbursement. This report underscores the need for standardized documentation practices, accurate use of ICD-10-CM codes, and proper querying techniques to support coding and documentation integrity.

Introduction

Encephalopathy is a broad term used to describe various conditions that result in an altered mental status (AMS) due to an underlying cause. It is a clinically significant and frequently encountered condition in modern healthcare and necessitates urgent recognition and intervention. Clinicians across specialties often face the challenge of differentiating encephalopathy from other causes of AMS, a challenge that can impact documentation and reimbursement. Accurate identification and documentation of encephalopathy not only promote correct diagnosis and treatment, but also play a pivotal role in improving clinical outcomes, enhancing patient safety, and ensuring appropriate coordination of care across healthcare teams.

According to the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS), encephalopathy is a term for “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure.”1 It is typically characterized by an altered mental state, which can range from mild confusion to deep coma, with manifestations like headache, fatigue, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, visual disturbance, or seizure.2–4 Encephalopathy is secondary to another condition; once the underlying cause is treated, the encephalopathy often resolves. However, there are also cases of chronic encephalopathy that result in permanent alteration of brain function. There are a wide variety of underlying causes, contributing to a long list of encephalopathy types with varying clinical indicators. Causes include infection, brain tumors, intracranial pressure, head injuries, strokes, seizures, vitamin deficiencies, and autoimmune conditions, among others.2 Understanding these distinctions is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Unfortunately, the cause is not always clear.4 Signs and symptoms of encephalopathy vary, but may include confusion, memory loss, sleepiness, behavior changes, hallucinations, tremors, difficulty breathing, and loss of consciousness, among others.2,3

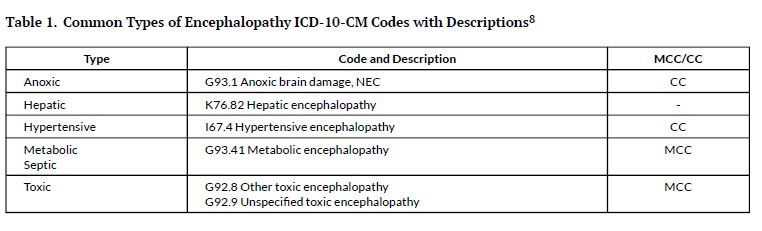

Some of the more common types of encephalopathy include anoxic, hepatic, hypertensive, metabolic, and toxic encephalopathies. Anoxic encephalopathy is caused by brain damage due to a lack of oxygen. Hepatic encephalopathy is linked to liver dysfunction, often seen in patients with cirrhosis, with a hallmark sign of an elevated ammonia level. Hypertensive encephalopathy is caused by extreme high blood pressure levels, with the effects most often reversible. Metabolic encephalopathy arises from metabolic disturbances within the body, such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, hypoglycemia, or acidosis. The clinical indicators for septic encephalopathy are the same as for sepsis, such as fever, elevated white blood cell count, and lactic acidosis, combined with altered mental status. Toxic encephalopathy occurs due to exposure to toxins, including drugs and poisons.5,6 An electroencephalogram (EEG) may support a diagnosis of toxic/metabolic encephalopathy, but is not considered mandatory to support it.7 Table 1 indicates the ICD-10-CM codes associated with these more common types.

Table 1.Common Types of Encephalopathy ICD-10-CM Codes with Descriptions[@472289]

Encephalopathy may be top of mind for many clinicians and coders, as it was a more frequent neurologic manifestation seen in COVID-19 patients.8 Other types of encephalopathy include chronic traumatic encephalopathy (F07.81), caused by repeated impacts to the head; hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (category P91), caused by a lack of oxygen to a baby’s brain shortly after birth; and Wernicke encephalopathy (E51.2), caused by a lack of vitamin B1.9 There are others still, such as postictal and uremic encephalopathy. In order to diagnose and document encephalopathy, it is important to compare the patient’s mental status to a baseline mental status. Standard laboratory evaluation of encephalopathy patients should include assessment of serum electrolytes, function tests, complete blood count (CBC), coagulation assays, and infectious disease workup.6 Encephalopathy will not typically show abnormalities on imaging, although patients with AMS should undergo a computer tomography (CT) scan to rule out hemorrhage or edema.4 Treatment should primarily be directed at addressing the underlying cause. Improvement in mental status following treatment of the underlying cause is a strong indicator that encephalopathy is present.

Searching the Literature

To capture the current complexities of encephalopathy diagnosis and documentation, the authors conducted a search of peer-reviewed articles, professional journals and publications, and associated blogs and Q&A forums moderated by coding and clinical documentation integrity (CDI) experts since 2015. Sources that focused primarily on the most common types were prioritized and search platforms included Google Scholar, EBSCOhost, AHIMA’s Body of Knowledge, ICD-10 Monitor, Coding Clinic, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and Association of Clinical Documentation Integrity Specialists (ACDIS) publications and forums, among others. Search terms were used to identify sources that addressed encephalopathy definitions, coding encephalopathy, CDI guidelines concerning encephalopathy, encephalopathy query recommendations, and encephalopathy-related reimbursement. Of the more than 400 articles reviewed, 26 were used to synthesize the challenges of documenting and coding for encephalopathy in this article.

Documentation of Encephalopathy

When encountering a patient with AMS, it is essential to ensure that encephalopathy is accurately documented, especially when clinical indicators suggest its presence. This includes verifying the condition throughout the record from the time of diagnosis to the discharge summary, with consistent documentation by all providers and a clear connection of the diagnosis with the underlying etiology.10 For example, if acute encephalopathy is documented in the assessment without a clinical picture of a confused or delirious patient, this is unclear documentation.11 Another example may be having toxic metabolic encephalopathy documented in several progress notes, but not included in the discharge summary.7 Consistently documenting the type and acuity of encephalopathy is crucial for accurate coding and treatment planning, including care transitions and interdisciplinary collaboration. Thorough and accurate documentation also supports early recognition and management of encephalopathy and performance improvement initiatives.

Querying for specificity may be needed to gain a thorough depiction of the patient’s encounter and ensure accurate reimbursement.3 Encephalopathy is a diagnosis vulnerable to clinical validation denials, which can be addressed through supportive documentation.12 According to an ACDIS poll, encephalopathy is in the top ten most queried diagnoses for CDI professionals.13 Clinical documentation queries should reflect the precise terms used by the physician. It may be helpful to have a physician liaison to assist with records that lack clinical supporting documentation. Queries offer an opportunity for clinicians to revisit clinical reasoning, refine differential diagnoses, and better communicate patient acuity to the entire care team. Querying may be necessary to gain clarification when only encephalopathy is documented.3 For example, if encephalopathy is present with fever, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and/or organ failure, it is appropriate to query for the specific type.14 The diagnosis must be supported with clinical indicators, both for the encephalopathy and type of encephalopathy identified. This includes documentation of one or more physical examinations that indicate the presence of AMS that differs from the patient’s baseline.15 Establishing baseline status may be challenging if documentation of the patient’s baseline is lacking.

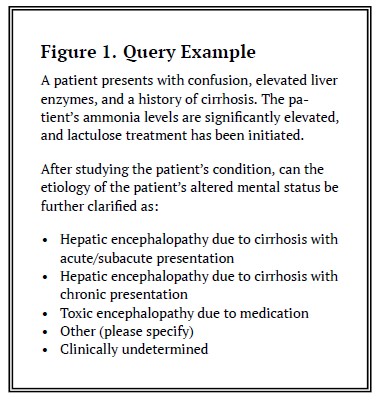

Consistent with compliant query practice, queries for documentation should avoid leading the physician. This may be done by using an open-ended format and/or avoiding contradictory options in a multiple-choice format. For example, if there are no clinical indicators for toxic encephalopathy such as an adverse effect of poisoning, it should not be listed as an option.15 Regardless of the final code, however, it may be beneficial to list different types of encephalopathy to align with clinical vocabulary. For example, if a patient is seen with sepsis, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection, and documented “worsening altered mental status”, it may be appropriate to query and list both metabolic encephalopathy and septic encephalopathy as options even though they both code to G93.41.16 Clinical indicators provided on the queries can assist physicians with specifying the type of encephalopathy when present. For example, when querying for hepatic encephalopathy as the potential type, elevated ammonia levels should be included.6 It is also appropriate to include options of “clinically unable to determine” and “other” to safeguard queries from additional scrutiny and possibly prevent a denial. An auditor may have concerns if all options listed have a positive financial impact on reimbursement.17 A query example can be seen in Figure 1. Additional query examples can be found in health information management resources, such as AHIMA’s Practice Brief on Clinical Validation.18

Figure 1. Query Example.

A practical example highlighting these documentation challenges was observed by one of the authors (AK) in a real-world case involving a 78-year-old patient admitted with altered mental status, dehydration, and severe hypernatremia. Despite the presence of significant clinical indicators, including AMS, high sodium levels, and improvement in mentation with fluid correction, the physician failed to link these findings with a diagnosis of metabolic encephalopathy. As a result, the diagnosis was not captured, and the case was later denied upon audit. A follow-up education session with the provider emphasized the importance of linking lab abnormalities, neurological changes, and clinical response to treatment with appropriate terminology to support accurate coding of encephalopathy.

Another personal example from one of the authors (AK) comes from a denied case where the patient presented with confusion, elevated BUN and creatinine, and a recent history of UTI. Although the provider documented “altered mental status” and “likely due to infection,” the term encephalopathy was never explicitly used, and no query was initiated. Upon retrospective review, the absence of the word “encephalopathy” resulted in the exclusion of a clinically supported diagnosis that would have impacted DRG assignment. Had the documentation included “septic encephalopathy” or a query been issued to clarify whether encephalopathy was present due to sepsis or metabolic disturbance, the case may have been upheld during audit.

These examples underscore the critical need for aligning clinical indicators with diagnostic language and ensuring that all components, including the initial presentation, progress notes, and discharge summary, reflect the diagnosis consistently. This illustrates the critical role CDI teams play in facilitating queries and bridging gaps in provider documentation, especially for high-risk diagnoses like encephalopathy.

Coding Challenges with Encephalopathy

Coders should be careful to look for the types and causes of encephalopathy, with indicators such as anoxia, alcohol or drug toxicity, liver disease, kidney failure, and metabolic disorders.3,4 In addition to differentiating types and underlying causes of encephalopathy, there are other coding challenges posed by the condition. Despite the complexity, there are no official coding guidelines that reference encephalopathy.19 Coding Clinic and other resources have addressed some of the coding challenges with types of encephalopathy:

-

Encephalopathy is not considered inherent to an acute cerebrovascular accident and thus should be reported as an additional diagnosis when documented and supported.20

-

Static encephalopathy may be reported in addition to epilepsy in a chronic state as other encephalopathy (G93.49).21 However, encephalopathy due to a postictal state is not coded separately, as it is considered to be integral to the seizure.3

-

Accurate coding of hepatic encephalopathy requires documenting the acuity of the hepatic condition (whether it is acute/subacute or chronic), as this affects the severity classification. Any underlying liver disease should be coded separately.9 A coma is not always present and must be documented as such for a coder to report the condition with coma.22

-

Encephalopathy due to hypoglycemia in a diabetic patient warrants metabolic encephalopathy (G93.41) as an additional diagnosis.23

-

Encephalopathy due to sepsis should be reported as metabolic encephalopathy.24 Although septic encephalopathy codes to metabolic encephalopathy, the term can still be used as a query choice.6

-

Toxic encephalopathy (category G92) originates from external exposures and sequencing rules are consistent with those of adverse effects and poisonings. If the medication was taken correctly and the patient experienced an adverse event, the toxic encephalopathy is coded first as the manifestation following by the appropriate adverse event code. If the medication was not taken correctly or the condition was due to a nonmedicinal or chemical substance, the appropriate poisoning code is listed first followed by the manifestation of toxic encephalopathy.6

If there is more than one type or cause of encephalopathy documented, more than one code should be used to fully describe the condition.3 For example, the Excludes 2 note under other and unspecified encephalopathy (G93.4x) indicates that additional codes may be used for alcoholic, hypertensive, or toxic encephalopathy as they are not included in G93.4x. This means both metabolic encephalopathy (G93.41) and toxic encephalopathy (category G92) may be coded together to more accurately represent the patient’s true severity of illness. If there is no specific encephalopathy code listed for the underlying cause, other encephalopathy or encephalopathy NEC (G93.49) should be used.9

It is also important to differentiate acute encephalopathy from delirium, as well as other causes of AMS.4 Although delirium and acute encephalopathy may appear clinically similar, differentiating them for workup and treatment of the underlying condition is imperative and may significantly impact reimbursement. Only encephalopathy is found on the major complication or comorbidity (MCC) list, specifically necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy, toxic encephalopathy, metabolic encephalopathy, and severe hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Delirium due to a known physiological condition or psychoactive substance use can be found on the complication or comorbidity (CC) list, along with the following types of encephalopathy: Wernicke’s, developmental and epileptic, hypertensive, and less severe levels of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Other and unspecified encephalopathy were previously on the MCC list, downgraded in 2018 to the CC list. Delirium not otherwise specified (NOS) is not considered a CC or MCC.25

Coders must pay careful attention to the specific terminology used by physicians, especially in distinguishing between encephalopathy with or without coma, and whether the encephalopathy is integral to another condition or should be coded separately. Accurate coding based on these guidelines is critical to ensuring that the medical record accurately reflects the patient’s condition and the care provided.

Addressing Encephalopathy Denials

Encephalopathy as a principal diagnosis or unspecified secondary diagnosis may leave a facility at high risk for claim denial. Denials often arise from the misconception that encephalopathy must be fully resolved prior to a patient’s discharge for the diagnosis to be considered valid. However, denials based on a single expectation of resolution overlook the clinical complexity of encephalopathy and can be challenged by providing a nuanced understanding of its types.

Encephalopathy can be classified as either transient or progressive, depending on its underlying cause. Transient forms, such as metabolic, septic, or toxic encephalopathy, are often responsive to treatment and may improve with the resolution of the underlying metabolic disturbance. However, even within these treatable types, symptoms may not always resolve completely by discharge. For example, a patient with uremic encephalopathy discharged to hospice due to renal failure would still be experiencing symptoms upon discharge. This underscores that the presence of ongoing symptoms does not invalidate the diagnosis of encephalopathy; instead, it reflects the chronic nature or incomplete resolution of the underlying condition.26

Progressive or chronic types, such as alcoholic, ischemic, or structural encephalopathy, are often irreversible, resulting in ongoing symptoms that persist beyond discharge. These forms of encephalopathy are less likely to see complete symptom resolution and instead represent an ongoing neurological condition. Denials that hinge on an expectation of total resolution fail to account for this inherent variation and the fact that encephalopathy diagnoses can validly reflect persistent or irreversible brain changes.26

When handling denials based on this misconception, it is essential to emphasize the importance of establishing the patient’s pre-existing baseline status. Knowing a patient’s baseline mental status can help differentiate between acute and chronic encephalopathy and provide evidence supporting the diagnosis of acute metabolic encephalopathy in the presence of pre-existing cognitive impairments. This distinction is critical in cases where the patient has pre-existing conditions, such as dementia, that may mask or mimic encephalopathic symptoms, complicating the diagnostic process.26

Adding a code for encephalopathy, without supporting documentation, on a resubmitted claim is a prevalent error found in high weighted DRG reviews.15 When appealing, it is important to know the clinical criteria and review the patient’s record for clinical indicators and appropriate treatment. In preparation of the appeal, it may be beneficial to add the NINDS description of encephalopathy: “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function.”1 This supports the claim through nationally recognized criteria, in alignment with the patient’s presentation and indicators.

Recommendations for Accurate Reimbursement of Encephalopathy

Unfortunately, encephalopathy is also a frequent denial subject due to lack of specificity and/or clear clinical indicators. Organizations can proactively address potential issues with encephalopathy reimbursement by ensuring accurate and complete documentation through training and tools. This may be done through a clinical validation process that includes a clinical validation team, education, physician engagement, and denials management.18 Organizations should consider the following:

-

A documentation guide that indicates:

-

baseline mental status,

-

deviations from baseline,

-

type of encephalopathy,

-

associated causal condition,

-

clinical indicators,

-

duration and severity of symptoms, and

-

response to treatment.

-

Physician training with examples of documentation that supports or refutes a diagnosis of encephalopathy.

-

Standardized query templates that include clinical indicators with potential types of encephalopathy and the associate cause(s).

-

A concise documentation template or phrase that clearly indicates the type and cause of the encephalopathy with associated clinical indicators.

One of the most effective strategies for reducing encephalopathy denials is the implementation of precise, etiology-specific documentation. Generic terms like “altered mental status” or “delirium” are often insufficient to support a code for encephalopathy. Instead, documentation should explicitly reference the type of encephalopathy and link it to a well-documented cause. For example, metabolic encephalopathy may stem from acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalance, or hypoglycemia. In such cases, clinical indicators such as creatinine, sodium, or glucose levels must be presented alongside the mental status changes. Similarly, toxic encephalopathy is typically triggered by drug toxicity or environmental exposure. The medical record should reflect the nature of the toxin, evidence of toxic levels in labs (eg, phenytoin level), and clinical symptoms such as confusion, agitation, or muscle rigidity. Documentation should also reflect the duration and severity of symptoms. For instance, mental status changes that resolve within hours without intervention may be less defensible than those requiring pharmacologic correction or prolonged monitoring. Moreover, it is crucial to describe the patient’s response to treatment (eg, “patient’s mental status improved after lactulose”), especially in hepatic or septic encephalopathy. A documentation guide may be used to assist physicians in clarifying the diagnosis and type of encephalopathy, outlining definitions, types, clinical indicators, and important documentation considerations.

Provider education is essential for improving the recognition and documentation of encephalopathy. Educational initiatives should include examples of documentation that support or refute encephalopathy. Providers should be encouraged to use clear terminology, such as “metabolic encephalopathy due to hyponatremia,” rather than non-specific terms. They should also be made aware that encephalopathy can be documented with other cognitive disorders, such as dementia, as long as there is clear evidence of deviation from the patient’s baseline mental status. Providers should be trained to document the baseline mental status, describe any deviations from baseline, and note whether mental status returns to baseline with appropriate treatment.

A variety of tools have been created to help with the documentation of encephalopathy. Standardized query templates can further support CDI and coding staff in obtaining clarification from providers. These templates should include pertinent clinical indicators, such as abnormal lab values, medication use, neurologic symptoms, and response to treatment. For instance, a query for toxic encephalopathy may cite elevated drug levels, AMS, and administration of reversal agents (eg, flumazenil), prompting the provider to specify whether toxic encephalopathy is present. Using condition-specific queries ensures that the documentation reflects the actual clinical scenario and aligns with coding guidelines.

Additionally, implementing documentation templates or phrases within the electronic health record can encourage providers to input required information systematically. It might read “[Acute/Chronic/Acute on Chronic] [Metabolic/Toxic/Metabolic-Toxic] Encephalopathy evidenced by [Clinical Indicators] due to [Etiology].”10

Conclusions

Encephalopathy is a complex condition that requires careful consideration of underlying causes for proper diagnosis and coding. Clear and consistent documentation of baseline mental status, the type of encephalopathy and associated cause, clinical indicators, and response to treatment can support accurate coding and reduce claim denials. Coders should also pay careful attention to tabular notes and related coding guidelines to ensure all codes are accurately captured. The development and use of standardized tools, such as query templates and documentation guides, can support consistent documentation practices, further minimizing the risk of denials. The accurate identification of the type of encephalopathy and its underlying cause is crucial in providing appropriate care and ensuring correct coding and reimbursement.

The implications of accurate encephalopathy documentation extend beyond coding and reimbursement; they also contribute to improved patient outcomes. Proper documentation aids in identifying the severity and progression of a patient’s condition, guiding clinical decisions for timely and appropriate interventions. By understanding the types of encephalopathy and the clinical indicators, healthcare professionals can improve the accuracy of documentation and coding, ultimately leading to better patient care. Establishing robust protocols for encephalopathy documentation, supported by ongoing education and clear guidelines, is critical to ensuring timely and effective treatment and overall quality of healthcare services.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this research.

Bibliography

-

-

-

-

4.

Reddy P, Culpepper K. Inpatient management of encephalopathy.

Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22102. doi:

10.7759/cureus.22102. PMID:35291547

-

-

6.

Valdez D. Taking the mystery out of encephalopathy. In: ACDIS Annual Conference. ; 2018.

-

-

8.

Shah VA, Nalleballe K, Zaghlouleh ME, Onteddu S. Acute encephalopathy is associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19 patients.

Brain Behav Immun-Health. 2020;8:100136. doi:

10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100136. PMID:32904923

-

9.

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.; 2024.

-

-

-

-

13.

Association of Clinical Documentation Integrity Specialists (ACDIS). ACDIS update: ACDIS poll reveals members’ top 10 queried diagnoses. CDI Strategies. 2018;12(16).

-

14.

Pinson R. Q&A: Encephalopathy due to UTI versus metabolic encephalopathy due to UTI. CDI Strategies. 2018;12(55).

-

15.

Livanta QIO. Higher-weighted diagnosis related groups (HWDRG) validation - Encephalopathy. The Livanta Claims Review Advisor. 2022;1(9).

-

-

17.

ACDIS. From the forum: Denial proofing queries. CDI Blog. 2018;11(181).

-

-

19.

CMS. ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting.; 2024.

-

20.

American Hospital Association (AHA). Encephalopathy associated with cerebrovascular accident. Coding Clinic. 2017;Second Quarter(4).

-

21.

American Hospital Association (AHA) . Static encephalopathy due to epilepsy. Coding Clinic. 2021;Second Quarter(8).

-

22.

American Hospital Association (AHA) . Hepatic encephalopathy. Coding Clinic. 2016;Second Quarter(3).

-

23.

American Hospital Association (AHA) . Encephalopathy due to diabetic hypoglycemia. Coding Clinic. 2016;Third Quarter(3).

-

24.

American Hospital Association (AHA) . Encephalopathy due to sepsis. Coding Clinic. 2017;Second Quarter(4).

-

-

26.

Frady A. Q&A: Denials for encephalopathy. CDI Strategies. 2018;12(39).