Download PDF

Abstract

Background

Healthcare teams rely on interprofessional collaboration (IPC) to improve patient outcomes, yet students often struggle to grasp the importance of interprofessional education (IPE). The University of Louisiana at Lafayette developed IPHE 310, an interprofessional course for Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and Health Information Management (HIM) students, aligning with Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) guidelines. Despite curricular revisions, student evaluations revealed ongoing confusion about the relevance of interprofessional education (IPE) and a disconnect between disciplines. This article reports the qualitative phase of an explanatory mixed methods study which examined these challenges by assessing student readiness for IPC and exploring BSN and HIM students’ perceptions of IPE.

Methods

The qualitative phase of the study involved the analysis of focus group discussions with students who attended the educational intervention, the “IPE is Key” workshop, using a semi-structured interview guide informed by prior IPE research. Focus group data were analyzed using the Scissor and Sort method, ensuring reliability through peer coding and member checking.

Results

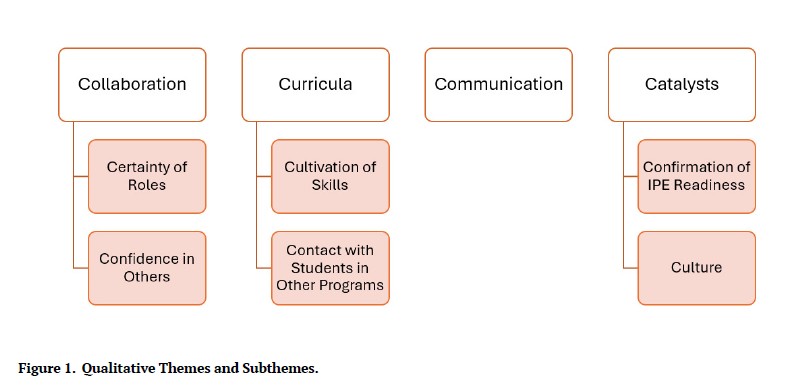

Findings revealed four overarching themes with six subthemes: (1) Collaboration (certainty of roles, confidence in others), (2) Curricula (cultivation of skills, contact with students in other programs), (3) Communication, and (4) Catalysts (confirmation of readiness, culture). Participants emphasized that early, structured exposure to interprofessional roles fosters teamwork, trust, and respect. They advocated for increased integration of IPE across curricula and hands-on activities to reinforce IPC competencies.

Conclusions

This study underscores the need for early and continuous IPE exposure to enhance students’ understanding of IPC. While the “IPE is Key” workshop improved readiness, focus group findings suggest that sustained, structured interactions across disciplines are essential for fostering collaborative competencies. Future research should explore long-term impacts of IPE interventions and strategies to bridge the gap between clinical and non-clinical health professions.

Introduction

Healthcare teams are composed of individuals with varied backgrounds and expertise, shaped by discipline-specific standards and traditional, cultural, and organizational norms.1 Effective collaboration requires a shared understanding of roles and responsibilities to support team-based care.2 However, healthcare professionals who lack training in team-based care may struggle to adapt.3

Interprofessional education (IPE) allows students in health professions to learn about, with, and from their peers, fostering collaboration and teamwork.4,5 IPE has gained widespread adoption, with 92% of U.S. medical schools incorporating it into their curricula.6 Research indicates that early exposure to interprofessional learning cultivates understanding, respect, and improved patient care.7,8 By training students to communicate effectively, appreciate a variety of professional roles, and apply ethical principles, IPE strengthens healthcare delivery and enhances patient outcomes.5,9

Faculty at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette developed IPHE 310: Ethical and Legal Tenets of Healthcare, an interprofessional course for Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and Health Information Management (HIM) students aligning with IPEC guidelines to meet BSN accreditation standards and prepare students for future collaboration.10 Despite course revisions, student evaluations revealed ongoing confusion about IPE’s relevance and a disconnect between nursing and HIM students, likely due to differences in clinical exposure and perceived roles. This two-phase explanatory mixed methods study investigated these challenges, assessing student readiness for interprofessional collaboration (IPC) and exploring BSN and HIM students’ perceptions of IPE.

The quantitative phase of the study included an assessment of BSN and HIM students’ attitudes and readiness for IPE before and after a three-hour IPE workshop titled “IPE is Key.”10 The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS), a tool used to evaluate students’ attitudes toward and readiness for IPC and IPE, was used for data collection.11 Paired samples t-tests were conducted to evaluate IPE readiness before and after the workshop, revealing a statistically significant overall improvement (p < .001).

In the study’s second phase, students’ experiences with IPE and IPC were explored. This article presents the findings of the second phase of the study, the themes of which add context and provide deeper insight into the results from our previously-reported quantitative study.10

Methods

Following approval from University of Mississippi Medical Center’s institutional review board (IRB; #2023-378), students were informed of “IPE is Key” and details of the study. The IRB granted permission for a waiver of documentation of informed consent, as the research posed no more than a minimal risk to participants. Prior to each focus group session, participants were verbally informed about the study’s purpose, potential risks and benefits, session duration, confidentiality measures, and their voluntary participation rights. By choosing to participate, individuals provided their consent. Although signed consent was not required, verbal consent was obtained by each participant and documented in a consent log maintained by the researcher.

Students who participated in the “IPE is Key” workshop (N=109) were recruited for the study’s second phase by asking them to indicate their interest in participating in a focus group discussion. To ensure maximum variation of sampling, participants for two virtual focus groups of BSN and HIM students were purposefully selected from the volunteers.

As the study intervention, the workshop introduced teamwork, communication, roles and responsibilities, and values and ethics,6 and improved students’ readiness for IPE. Focus group one included HIM and BSN students who attended the “IPE is Key” workshop and completed the fall IPHE 310 course; the group included four HIM students (three seniors and one junior) and two BSN students (one senior and one junior). The second focus group consisted of students who participated in the workshop but had not completed the fall IPHE 310 course, which included four sophomore HIM students and two senior BSN students. Each session lasted approximately 75 minutes and was recorded and transcribed. To maintain confidentiality, all personally identifiable information was removed from transcripts. Audio recordings were deleted after the transcripts were edited.

Focus group data were collected utilizing a semi-structured interview guide, with questions informed by prior IPE research and the findings from phase one of the study. The guide for focus group one included a question exploring how the “IPE is Key” workshop may have enhanced the IPHE 310 course, while this question was omitted from the focus group two guide (Appendix A).

Results

Data were analyzed via a thematic analysis framework, a qualitative research design emphasizing the identification and interpretation of patterns or themes within the data. Transcript data were analyzed using the Scissor and Sort method,12 systematically reviewing transcripts for content relevant to the research questions. This method was selected due to its efficiency in sorting large amounts of qualitative data. The researcher (TJB) thoroughly reviewed the transcripts and conducted comprehensive coding. Each category and subcategory was assigned a unique color, and excerpts representing similar concepts were grouped together. Key themes were identified and supporting quotes were selected to illustrate the findings. Data from both focus groups were initially coded separately, but commonalities between the groups were later identified.

An experienced external peer coder independently coded the transcripts before comparing results with the researcher. This process ensured consistency, transparency, and trustworthiness of the analysis, while minimizing potential researcher bias. Member checking was conducted by providing participants with a summary of the findings for their review.13

Findings revealed four overarching themes and six subthemes (Figure 1). While there were common themes found in the two groups, unique elements in each group also emerged. Themes identified from the focus group data answered the following research question: “How does a sample of BSN and HIM students describe their experiences with and perceptions of IPE and IPC (Appendix B)?”

Figure 1.Qualitative Themes and Subthemes.

Theme One: Collaboration

Participants highlighted the importance of collaboration in healthcare settings, emphasizing how professionals build on each other’s knowledge and work cohesively toward shared goals. Participants recognized that effective teamwork fosters mutual support, with each profession relying on the strengths of others to enhance patient care and workplace efficiency. From this, the subthemes of roles certainty and confidence in others were identified in this overall theme of collaboration.

“…seeing different professions interact, how we saw the guest speakers that you had at the IPE workshop interact, and how they were all feeding off of each other and just adding onto each other sentences and just showing how cohesive everybody is and how important collaboration is in a workplace. … inspired everybody to be more accepting of everybody having different roles in a workplace (Participant FG2C).”

“We rely on each other. In a perfect world, I feel like it would be everybody just using each other as a backbone. We all work together and lean on each other (Participant FG1E).”

Subtheme One: Certainty of Roles. Focus group participants emphasized that early exposure to various roles fosters awareness and improves professionalism, while insight into others’ responsibilities leads to mutual respect and effective teamwork.

“The sooner that we expose ourselves to this massive expanse of positions, roles, and responsibilities, and we become cognitively aware of them, then we can start having an overall effect in how we practice what we do (Participant FG2A).”

“It was just a level of respect that he gained from understanding her role (Participant FG1E).”

Subtheme Two: Confidence in Others. Participants noted that trust and respect are interdependent. A deeper understanding of others’ roles fosters trustworthy collaboration. These comments highlight how trust in interprofessional collaboration increases confidence in others and is foundational to effective teamwork.

“I think in a healthcare setting, trust is really big. Trust lays the foundation for everything. If you don’t trust someone, things can go all wrong (Participant FG1C).”

“I think that, to some degree, there should be a level of trust and most definitely a level of respect. With that comes a level of understanding. So, if we don’t understand each other, then how can you really trust what somebody else is saying (Participant FG1E)?”

Theme Two: Curricula

The overarching theme of curricula emerged as participants in both focus groups emphasized the need for additional IPE integration to enhance learning and patient outcomes. They stressed IPC as a foundational element in their programs, rather than as isolated experiences. Hands-on activities in reinforcing competencies were mentioned, as was the importance of repeated, structured interactions across disciplines. The subthemes cultivation of skills and contact with students in other programs were also identified.

“More frequent smaller exposures to each other throughout the entire curriculum would be helpful (Participant FG1A).”

“By physically interacting, having these conversations, and going through these exercises, it’s clicking into place. That tells me these workshops need to be more frequent (Participant FG2A).”

Subtheme One: Cultivation of Skills. Participants stressed that repeated exposure to different professions enhances workforce readiness. Structured IPE opportunities were seen as essential for developing these skills before entering professional roles. These quotes support how IPE cultivates communication, trust, and collaboration during the foundational years.

“The more that we interact with different professions in our education and from a learning standpoint, I think, would prepare us to enter the workforce at a higher level than if we had none at all (Participant FG2A).”

“Everybody needs to start building trust and respect in the foundational years (Participant FG2C).”

Subtheme Two: Contact with Students in Other Programs. Focus group participants stressed the need for early, consistent IPE exposure, emphasizing engagement with other health professions. They noted that structured, small-group interactions enhance collaboration and readiness, while limited exposure to other disciplines was seen as a barrier. These insights highlight the importance of frequent, intentional, interdisciplinary engagement.

“Integrating us into these small groups, even on a semester level, would be strongly beneficial to the overall mission objective (Participant FG2A).”

“It would have helped just to have that exposure. Because naturally, if you are exposed to a group of people more than once, you will feel a little bit more comfortable the second time (Participant FG1A).”

Participants stressed the value of interacting with pre-medical students and preferred using simulations and real-life scenarios for IPE activities.

“It would be really helpful to get exposed to other majors …like pre-med students (Participant FG1A).”

“I think multiple formats [of IPE] have to come into play because that is going to make something stick or have an individual have that epiphany moment (Participant FG2A).”

“I think a class or a workshop, or maybe, a simulation would also be fun, like a scenario. I think a lot of people would like to participate in that (Participant FG2B).”

Theme Three: Communication

The theme of communication emerged as participants recognized the importance of enhancing interpersonal skills for effective teamwork. Participants emphasized the necessity of adapting communication styles to work with diverse professionals, highlighting the role of IPE in refining these essential skills.

“I feel like a lot of people know and understand that they will have to work as a team. They just might not know the extent of it quite yet (Participant FG2C).”

“You have to adapt, and you know, you have to learn how to communicate with different kinds of people (Participant FG1A).”

Theme Four: Catalysts

The theme of catalysts refers to the positive catalyzing or accelerating effect of IPE experiences in promoting awareness, collaboration, and skill development. Participants from both focus groups identified positive changes in attitudes and perceptions as a result of the IPE activities.

“[Referring to an IPE in-class activity] That definitely was very eye-opening and made me have more of a positive idea about their major (Participant FG1A).”

“I think it would’ve helped the [IPHE 310] class run a little bit smoother when it came to us by communicating and working together because we would already have an idea of what the other major did and how they help each other work together. So yeah, it would’ve helped with better communication (Participant FG1D).”

Subtheme One: Confirmation of Readiness. Focus group participants recognized that readiness for IPE is essential for effective learning, emphasizing the importance of attitude, preparedness, and willingness to collaborate. They highlighted that engagement could stem from both interest and opportunity.

“That willingness to help others and collaborate is necessary (Participant FG2C).”

“Readiness definitely can come from an “I’m bored,” or “I’m interested” kind of scenario (Participant FG2A).”

Subtheme Two: Culture. Participants observed that limited exposure to other health professions may contribute to professional silos and reinforce negative perceptions. They emphasized the need for mutual respect and a broader understanding of each profession’s role to foster a more collaborative culture.

“A lot of the emphasis is on doctors respecting what we do. And it’s not really emphasizing how we should respect what others do (Participant FG2B).”

“I’m so used to that insulated environment, but exposure to the nursing students definitely changes that (Participant FG1A).”

Discussion

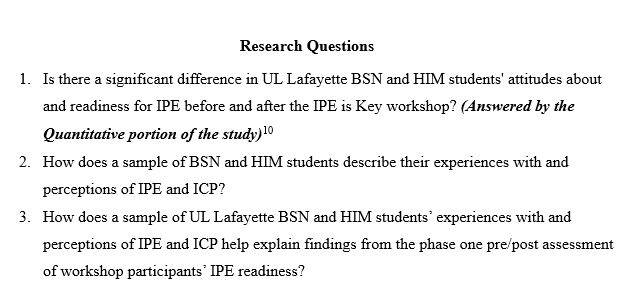

Focus Group Participants’ Explanations of Phase One Findings

This study explored how BSN and HIM students’ experiences with and perceptions of IPE and ICP could provide insight into the quantitative findings from phase one of this study, which revealed a significant increase in readiness for IPE after participation in the “IPE is Key” workshop.10 The sequential mixed-methods design of this phase ensured that the qualitative responses collected from the focus group illuminated the pre/post workshop assessment results, deepening the understanding of the quantitative findings and ultimately addressing the third research question: “How do a sample of UL Lafayette BSN and HIM students’ experiences with and perceptions of IPE and ICP help explain findings from phase one pre/post assessment of workshop participants’ IPE readiness (Appendix B)?”

Although the overall pre/post scores from phase one revealed a significant increase in IPE readiness (p<.001), analysis of other subcategories and specific statements on the assessment did not show significance (p=0.078; p=0.271).10 Focus group participants were asked why they thought the findings suggested no clear evidence of effect for the statement, “Shared learning before graduation will help me become a better team worker.” Their responses suggested a ceiling effect, meaning that most students strongly agreed with the statement before the workshop, leaving little room for further improvement in their post-workshop responses.

“I knew going in that I’m going to have to communicate between different professions, and I knew going out that I’ll have to communicate between different professions (Participant FG2C).”

“Going into the workshop, I knew, and I know, that it is important for us to collaborate with each other. I know that (Participant FG1A).”

Participants were asked about the significant increase in post-workshop assessment scores compared with pre-workshop scores for the statement, “Shared learning will help me think positively about other health professionals.” Participants explained and supported these findings with positive comments about their IPE experiences and beneficial changes in their attitudes.

“[IPE] really personifies the people behind the major and increases your attitude towards them (Participant FG1A).”

“It really is just everybody feeds off each other (Participant FG2C).”

Participants noted the significant post-workshop increase in mean agreement scores for the statement, “Shared learning with other healthcare students will help me communicate better with patients and professionals.” They recognized this as evidence of shared learning’s role in improving communication skills among health profession students.

“I think we’re adding tools to the toolbox…because there’s so many different ways we can communicate (Participant FG2A).”

“It helps us communicate with other people because it just kind of forces us out of our comfort zone (Participant FG1B).”

Participants commented on the significant increase in post-workshop agreement scores for the statement, “For small group learning to work, students need to trust and respect each other.” They found the statement profound and strongly agreed with the findings.

“I feel like that is the most true statement. If there is one statement that could encapsulate working with the group (Participant FG1A).”

“Very true (Participant FG2C).”

When asked about their thoughts on the significant increase in overall pre- and post-workshop mean scores, both focus group participants noted that the “IPE is Key” workshop was valuable. Many described the experience as “eye-opening” and strongly agreed on its benefits.

“It’s eye-opening, I guess, to see how everybody really does work together, and just how important everybody is to the overall picture (Participant FG2C).”

“It opened up a big door for collaboration and communication (Participant FG1E).”

Student responses suggest that completing the “IPE is Key” workshop before IPHE 310 may enhance students’ understanding and respect of other professions and promote a more positive course experience. Overall pre-workshop IPE readiness scores were lower for those who had completed IPHE 310, possibly due to the time gap between completion of the course and the “IPE is Key” workshop, with one participant noting that over a year had passed since their last engagement with students in other professional programs. This contrasts with research suggesting prior IPE exposure fosters more positive attitudes.14 However, all participants emphasized the importance of collaboration in healthcare teams, highlighting roles, responsibilities, trust, and respect. Their recognition of IPE’s value aligns with a 2016 IPEC report linking IPE to improved healthcare delivery and patient outcomes.9

As reported in previous research findings, student participants appreciated cross-professional interactions and advocated for more integration, stressing the need for early and continuous IPE exposure in the formal curriculum, aligning with research that has suggested IPE offered early in an academic program fosters interprofessional understanding and respect.7,8,15Additionally, participants reinforced prior research findings that IPE enhances teamwork and communication skills.16–18

Participants suggested that early interaction with students from other health professions could help reduce negative stereotypes and break down professional silos, which supports the findings of Moote et al.19 Those researchers studied the impact of an early IPE program that enhanced student engagement and satisfaction while promoting the development of professional identity without stereotypes or biases.

Under the theme of catalysts, the subtheme of readiness emerged, as participants emphasized the role of attitudes, preparedness, and willingness to learn in achieving successful learning outcomes. Consistent with these findings, previous research has shown that students’ attitudes, readiness for IPE, and preparedness are strong predictors of their willingness to engage in interprofessional education.7,20–24 Participants noted a ceiling effect on the statement, “Shared learning before graduation will help me become a better team worker,” as focus group members already agreed, aligning with findings of other studies using RIPLS.25

They emphasized that increased IPE exposure improves communication, fosters positive attitudes, and builds trust and respect in small-group learning. Focus group one, which included students who had previously completed the IPHE course, suggested enhancing this IPE course by adding more group interactions, social events, and overlap in the BSN/HIM curriculum content. They recommended offering the “IPE is Key” workshop early to better prepare students for future IPE coursework and activities.

Conclusions

The first (quantitative) phase of the current study revealed a significant improvement in the overall attitudes and IPE readiness among BSN and HIM students at UL Lafayette before and after the “IPE is Key” workshop, while the present (second, qualitative) phase further explained these findings. Focus group participants expressed the value of increased interaction with peers from other health professions. Study findings underscore that early and continuous integration of IPE into health professions curricula is crucial for meeting programmatic accreditation standards and cultivating the collaboration and teamwork skills essential for professional success and improved patient outcomes. Future research should explore long-term impacts of IPE interventions and strategies to bridge the gap between clinical and non-clinical health professions.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

The authors received an internal faculty grant from the Student Center for Research, Creativity, & Scholarship (SCRCS) at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in the amount of $5,000 for food, activity supplies, and prizes.

Ethics Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at University of Mississippi Medical Center (2023-378).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ottis Lee Brown, Jr., DHA, for his assistance with the peer coding review of this research.

Appendices

Appendix A.

Appendix B.

Bibliography

-

1.

D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks.

J Interprof Care. 2005;19 Suppl 1:116-131. doi:

10.1080/13561820500082529. PMID:16096150

-

2.

Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care.

NAM Perspectives. Published online October 2012. doi:

10.31478/201210c

-

3.

Crampsey EW, Rodriguez K, Cohen-Konrad S, et al. The impact of immersive interprofessional learning on workplace practice.

J Interprof Educ Pract. 2023;31:100607. doi:

10.1016/j.xjep.2023.100607

-

4.

Atwa H, Abouzeid E, Hassan N, Nasser AA. Readiness for interprofessional learning among students of four undergraduate health professions education programs.

Adv Med Educ Pract. 2023;14:215-223. doi:

10.2147/AMEP.S402730

-

-

-

7.

Alruwaili A, Mumenah N, Alharthy N, Othman F. Students’ readiness for and perception of interprofessional learning: A cross-sectional study.

BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):390. doi:

10.1186/s12909-020-02325-9

-

8.

Guraya SY, Barr H. The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34(3):160-165. doi:

10.1016/j.kjms.2017.12.009

-

-

10.

Beebe T, Franklin E, Hazelwood A. Interprofessional Education Readiness with Undergraduate Nursing and Health Information Management Students at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Advances in Health Information Science and Practice. 2025;1(1):1-10. doi:

10.63116/QEKZ6869

-

11.

McFadyen AK, Webster V, Strachan K, Figgins E, Brown H, McKechnie J. The readiness for interprofessional learning scale: A possible more stable sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS.

J Interprof Care. 2005;19(6):595-603. doi:

10.1080/13561820500430157

-

12.

Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications, Ltd; 2007.

-

13.

Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. SAGE Publishing; 2018.

-

14.

Huebner S, Tang Q, Moisey L, Shevchuk Y, Mansell H. Establishing a baseline of interprofessional education perceptions in first-year health science students.

J Interprof Care. 2021;35(3):400-408. doi:

10.1080/13561820.2020.1729706

-

15.

Imafuku R, Kataoka R, Ogura H, Suzuki H, Enokida M, Osakabe K. What did first-year students experience during their interprofessional education? A qualitative analysis of e-portfolios.

J Interprof Care. 2018;32(3):358-366. doi:

10.1080/13561820.2018.1427051

-

16.

Carney PA, Thayer EK, Palmer R, Galper AB, Zierler B, Eiff MP. The benefits of interprofessional learning and teamwork in primary care ambulatory training settings.

J Interprof Educ Pract. 2019;15:119-126. doi:

10.1016/j.xjep.2019.03.011

-

17.

McGuire LE, Stewart AL, Akerson EK, Gloeckner JW. Developing an integrated interprofessional identity for collaborative practice: Qualitative evaluation of an undergraduate IPE course.

J Interprof Educ Pract. 2020;20:100350. doi:

10.1016/j.xjep.2020.100350

-

18.

Stickley L, Gibbs D. Physical therapy and health information management students: Perceptions of an online interprofessional education experience. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2020;18(Winter):1f. PMID:33633516

-

19.

Moote R, Anthony C, Ford L, Johnson L, Zorek J. A co-curricular interprofessional education activity to facilitate socialization and meaningful student engagement.

Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021;13(12):1710-1717. doi:

10.1016/j.cptl.2021.09.044

-

20.

Filies GC, Frantz JM. Student readiness for interprofessional learning at a local university in South Africa.

Nurs Educ Today. 2021;104:104995. doi:

10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104995

-

21.

Melnyk BM, Dabelko-Schoeny H, Klakos K, et al. POP care: An interprofessional team-based healthcare model for providing well care to homebound older adults and their pets.

J Interprof Educ Pract. 2021;25:100474. doi:

10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100474

-

22.

Murray M. The impact of interprofessional simulation on readiness for interprofessional learning in health professions students.

Teach Learn Nurs. 2021;16(3):199-204. doi:

10.1016/j.teln.2021.03.004

-

23.

Numasawa M, Nawa N, Funakoshi Y, et al. A mixed methods study on the readiness of dental, medical, and nursing students for interprofessional learning.

PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0255086. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0255086

-

24.

Olenick M, Allen LR. Faculty intent to engage in interprofessional education.

J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:149-161. doi:

10.2147/JMDH.S38499

-

25.

Torsvik M, Johnsen H, Lillebo B, Reinaas LO, Vaag J. Has “The Ceiling” rendered the readiness for interprofessional learning scale (RIPLS) outdated?

J Multidiscip Healthc. Published online 2021:523-531. doi:

10.2147/JMDH.S296418