Download PDF

CE Quiz

Abstract

Background

Some research on social determinants of health (SDOH) has suggested that patient health literacy (HL) or comprehension can influence health outcomes, while other recent studies have not observed strong connections between those variables. Previous research has utilized various screening tools to assess patient HL, with varying success.

Methods

In this three-phase study, the authors assessed the “readability” of various common patient health information documents and forms used by prominent US-based healthcare organizations and requestors, including authorizations and privacy notices, according to the Flesch-Kincaid and Flesch Reading Ease scales.

Results

The results showed that the documents examined had readability scores higher than the average American’s literacy level.

Conclusions

Confirming anecdotal data, this research supports the conclusion that many forms signed by American patients are above their average reading level and therefore they may not have a full understanding of what they are signing, even when requesting that records to be sent to others.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, various health organizations have worked to mitigate persistent, universal health inequalities.1 These disparities, referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH), can include racial, ethnic, and cultural differences as well as social, political, and environmental conditions.2 While many healthcare organizations have taken steps to better understand, classify, and reduce the disparities, there is still significant progress needed to remove these barriers.

Among the various SDOH factors, health literacy (HL) is one that can impact the entire patient experience.3–5 Typically described as “a set of skills needed to function in the healthcare environment,”4(p1228) HL has been evaluated in previous literature for its potential influence on health outcomes. Initially and in the early 2000s, HL was thought to be linked to positive health outcomes,5–7 with many professional healthcare agencies illuminating the need for greater HL.8–10 Much of the previous HL research focused on literacy and patient outcomes like quality of life or mortality.11 In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasized that various socioeconomic factors, including cultural traditions that do not place a high regard on literacy, can have a negative impact on children’s health and development.12 However, more recent research has shown mixed results. In a 2019 systematic review on HL and health outcomes among patients with long-term conditions, the results did not show strong connection between the variables.11,13–15 Yet several other studies have continued to find positive links between HL and some patient outcomes.3,16–18

There are several measures utilized to assess HL, which include the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT),19,20 the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM),21 the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA),22 and the Newest Vital Sign (NVS).23 DeWalt et al4 previously conducted a systematic literature review of the first three measures, concluding that they appeared to all measure the same basic constructs of HL. Another literature review by Voigt and Brütt24 found that, in six of seven included studies that compared patients’ self-reported level of HL with a level assessed by their provider, there was notable discrepancy. The authors said, “Most of the reviewed studies either concluded a significant overestimation by HCPs or a poor agreement between patients’ HL assessment by patients and HCPs.”15

General Literacy and Health Literacy

Our study is posited on the assumption that HL is positively correlated to general literacy—if a person can read, they have the potential for greater HL. Some early research has supported this idea, finding people with lower literacy levels were 1.5 to 3 times more likely to have adverse health outcomes compared with those with higher literacy.4

Research on general literacy is extensive. While the results again show variance, one research study suggested that nearly one of five U.S.-based individuals cannot read.25,26 The average American is believed to read at around the eighth or ninth grade level.27 This reinforces the need for patient-facing material28 and other consent material to be written at a level that patients are able to understand.16

There are multiple measures used to assess content readability, including the Raygor Estimate, SMOG, Fry, FORCAST, and Gunning Fog.29 One of the most common tests to determine readability is the Flesch-Kincaid index.30 The Flesch-Kincaid readability test looks at average sentence length (ASL; the number of words divided by the number of sentences) and average number of syllables per word (ASW; the number of syllables divided by the number of words). The Flesch-Kincaid equation is: (.39 x ASL) + (11.8 x ASW) – 15.59.31 The results provide a score equivocating to the U.S. grade level. Another related scale is the Flesch Reading Ease calculation, which uses the following equation: 206.835 – (1.015 x ASL) – (84.6 x ASW).31 In this scale, a higher number score would indicate that the material is easier to read, with the most readable document being a score of 100. We report both the Flesch-Kincaid and Flesch Reading Ease, but focus on the former because it is one of the most ubiquitous methods available32 and has been utilized in previous medical studies.33–35

This research examined the reading levels of various patient-facing documents as follows:

-

Release of information authorization documents;

-

Consent to Treat, Notice of Privacy Practices, and Patient Health Information (PHI) Access forms; and

-

Third-party release of information authorizations, such as those from the Social Security Administration.

Prior to this research, we sought ethical approval from the Fort Hays State University Institutional Review Board (Ref. # 24-0040). The study was deemed to not be human subject research.

METHODS

Initially, we sought to examine HL by evaluating the readability of one of the more commonly used patient-facing forms: release of information authorizations. Release of information (ROI) is the process where patients request their health records be transmitted to themselves or another entity—another provider, government agency, insurance company, attorney, and so on. Some requests, like when records are transmitted to other healthcare providers, can be completed without the need for authorizations. Most other requests require patients to sign authorization forms.

The patient-signed authorization forms required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule (42 CFR 164.508(b)(4)) consist of seven key elements and four required statements.36 The required statements serve to inform patients of their rights and include an expiration date, revocation statement, redisclosure statement, and conditioning statement. The latter three statements are required to convey their point, but the Privacy Rule does not mandate specific verbiage or format.

Our hypothesis was that the ROI authorizations used by top hospitals would be written at an eighth-grade or lower reading level, allowing for the greatest consumption by patients. This hypothesis was based on HIPAA Privacy Rule’s requirement that authorizations should be written in plain language.

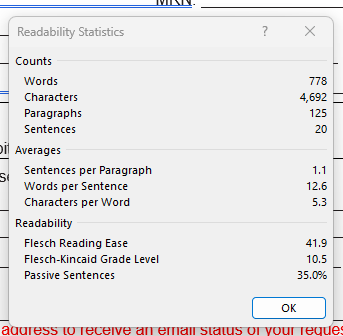

Using the 2023 Newsweek list of the top 150 best hospitals in the United States,37 we obtained ROI authorization forms from all facility websites (see Appendix 1). We did this by searching the official websites of these facilities for the forms. As most forms were in portable document format (PDF), we used Adobe Acrobat Version 2024 to convert the documents into a Microsoft Word document. We then utilized Microsoft Word 365’s built-in readability tests to determine the Flesch-Kincaid and the Flesch Reading Ease calculations for these authorizations, as well as total page count. For more detail, see Figure 1 or view Microsoft’s tutorial, which can be found by searching “Readability Statistics” at https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/.

Figure 1.Example of Microsoft Word’s Readability Reporting, as performed on the manuscript for this study report.

We next hypothesized that other common forms, such as Consent to Treat, Notice of Privacy Practices, and Patient Health Information (PHI) Access Forms would be written at an eighth-grade or lower reading level. We used the same process described above (ie, searching the official facility website for the form, converting the form to DOC, etc.); however, we were unable to locate all three forms online for all 150 of Newsweek’s listed hospitals. After excluding unavailable forms, we assessed 103 Consent to Treat forms, 135 Notice of Privacy Practices, and 141 PHI Access forms. We again utilized Microsoft Word’s features to obtain the Flesch-Kincaid score, Flesch score, and page counts.

Finally, we hypothesized that third-party authorizations would have a similar reading level as the hospital-created forms. To explore this, we examined forms from requestor agencies to determine whether their forms (often created by attorneys and insurance companies) exceeded eigth- or ninth-grade reading level. We first identified those agencies that submitted the highest number of ROI requests to a large nationwide release of information service provider. This company is required to retain the request form by law, so that database of forms was used to obtain the agency-specific request forms. We identified the 80 most frequently represented agencies that requested records in 2023. From that sample pool of 80 agencies, we located forms from 63 agencies in the database. Many of the agencies utilized healthcare facility-specific-created forms for their ROI process as opposed to creating their own forms. The same PDF to DOC conversion process was used, as were the MS Word readability tests.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows results from the initial analysis, in which authorization forms from 150 hospitals were assessed. The mean Flesch-Kincaid grade level for these authorizations was 12.17 (SD = 2.0). The mean Flesch Reading ease score was 37.40 (SD = 8.5), and the mean number of pages was 1.81 (SD = 0.9). Only one facility in the Phase 1 study had a form with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level score under 8 and a Flesch Reading Ease score above 60.

Table 1.Results of the Flesch Reading Ease Scale, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Assessment, and Number of Pages for Authorization Forms from 150 Healthcare Organizations.

| Measure |

Mean |

Mode |

Standard Deviation |

| Flesch Reading Ease |

37.4 |

21.2 |

8.5 |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade |

12.2 |

12.4 |

2.0 |

| Pages |

1.8 |

2 |

0.9 |

Table 2 shows the results from the second analysis, in which 103 Consent to Treat forms, 135 Notice of Privacy Practices, and 141 PHI Access forms were assessed. All three forms had a mean Flesch-Kincaid grade level score above 12. The Consent to Treat form had a mean Flesch-Kincaid grade level score of 13.30 (SD = 2.6), a Flesch Reading Ease score of 37.28 (SD = 10.09), and was 4.6 pages in average (SD = 5.4). The Notice of Privacy Practices had a mean Flesch-Kincaid grade level score of 12.09 (SD = 1.5), a Flesch Reading Ease of 41.56 (SD = 8.8), and an average of 6.5 pages (SD = 4.3). The PHI Access Form scored similarly, with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level mean of 12.48 (SD = 2.0), a Flesch Reading Ease mean score of 36.26 (SD = 9.2), and an average number of pages of 1.8 (SD = 0.9).

Table 2.Results of the Flesch Reading Ease Scale, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Assessment, Number of Pages for Consent to Treat (N=103), Notice of Privacy Practices (N=135), and PHI Access Forms (N=141).

| Form |

Measure |

Mean |

Mode |

Standard Deviation |

| Consent to Treat |

Flesch Reading Ease |

37.3 |

32.8 |

10.9 |

| |

Flesch-Kincaid Grade |

13.3 |

14.3 |

2.6 |

| |

Pages |

4.6 |

2 |

5.4 |

| Notice of Privacy Practices |

Flesch Reading Ease |

41.6 |

31.4 |

8.8 |

| |

Flesch-Kincaid Grade |

12.1 |

14.5 |

1.5 |

| |

Pages |

6.5 |

4 |

4.3 |

| PHI Access Form |

Flesch Reading Ease |

36.3 |

19.9 |

9.2 |

| |

Flesch-Kincaid Grade |

12.5 |

11.5 |

2.0 |

| |

Pages |

1.8 |

2 |

0.9 |

Table 3 shows our final analysis of 63 forms from third-party ROI requestors. The Flesch-Kincaid mean grade level was 11.42 (SD = 3.7), a Flesch Reading Ease score of 38.41 (SD = 16.1), and was 2.5 pages on average (SD = 1.7). Eight agencies had forms with Flesch-Kincaid scores below the commonly-accepted eighth-grade general literacy level.

Table 3.Results of the Flesch Reading Ease Scale, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Assessment, and Number of Pages for Authorization Forms from 63 Large Requestor Agencies.

| Measure |

Mean |

Mode |

Standard Deviation |

| Flesch Reading Ease |

38.4 |

33.7 |

16.1 |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade |

11.4 |

13 |

3.7 |

| Pages |

2.5 |

1 |

1.7 |

DISCUSSION

Based on the previous literature suggesting Americans have an average reading level around the eighth grade,26,29 the results of all three analyses of this study demonstrate that most patient forms are likely too difficult for many Americans to understand. None of our hypotheses were supported by the data. This was a surprise to us with regard to hospital-based forms; we hypothesized that top U.S. hospitals would have ROI authorizations and other patient-facing forms which comply with the Plain Language requirement.38 The results suggest that many of these forms are likely not understood or misunderstood by patients completing them due to a higher than expected reading level. Interestingly, our results indicated that the forms from third-party agencies had better readability scores than those from healthcare organizations. Of the three analyses, we believed this one had the most privacy implications. Patients are completing forms to authorize outside entities—attorneys, insurance companies, etc.—to access sensitive information. If a patient is unable to fully understand the form, informed consent could be compromised. While the mean scores still weren’t matched with the general reading level of most patients and, therefore, weren’t optimal, this sample of high-volume requestors managed to make their ROI authorizations more approachable than healthcare organizations.

The results of our research demonstrate that significant inequalities still exist in healthcare in relationship to HL. While the discussion about the role of SDOH in healthcare remains contested, numerous studies have found higher levels of HL correspond to better patient outcomes.4–8,11,12 As the American healthcare system is difficult to navigate even for professionals, increasing the accessibility of healthcare will result in new patient populations entering the American healthcare system. That is, those individuals who are currently reticent to seek healthcare services or previously underserved populations would have greater access to these services and bring with them unique communication needs.39 These patients may be encountering documents like authorization forms for the first time. Without sufficient HL, patients may not understand the consequences of signing such a document. We need to meet our patients where they currently are.

Authorization documents are intended to inform patients of their rights and risks; if a patient cannot understand the document, is the patient appropriately informed? The results of our study show that standardized documents and forms patients are often required to complete might be difficult for most patients to understand. Recent developments, such as changing standards for providing reproductive health and gender-affirming care,40 have increased the stakes for disclosing PHI. When coupled with a heightened emphasis on information sharing, the conditions for, and the consequences of, an unintended disclosure of PHI are considerably greater than before.

The interaction between a patient’s HL level and the readability of standard forms can negatively impact clinical outcomes and the patient experience. We know informed patients have better outcomes.3–5,41,42 Part of being informed is access to PHI, and if a patient has low levels of HL, there is a distinct possibility the patient may not access PHI because they are overwhelmed or do not understand the ROI process. Further, patients may not request the specific PHI they need, as they might not understand the medical terminology used. This would result in a less informed patient. The inability to access the specific information needed may also result in dissatisfaction with a healthcare provider and a possible access complaint to the Office of Civil Rights (OCR).

When considering the design and readability of forms, it is also important to consider how patient-related factors can mitigate or exacerbate a patient’s level of HL, including native language and complex physical needs. Language proficiency has the potential to affect a patient’s lack of HL. Multilingual patients are likely not equally proficient in each language; it would be reasonable to assume that the proficiency and literacy decline with each subsequent language learned.43–45 A patient may have a higher HL in their native language but a lower HL in second or subsequent languages. In an ideal environment, ROI authorizations and other critical documents would be readily available in a patient’s native language. We realize this isn’t the case everywhere; this reality only emphasizes the importance of documents being written in plain language. Moreover, patient populations with more complex needs may be less likely to ask for assistance in reading a form. For instance, an aging patient may not admit needing, let alone request, documents in large print. Patients with lower socioeconomic status may be unable to access online-only request documents. Neurodivergent patients may also struggle and become overwhelmed by tiny print and little whitespace. Mental health patients with paranoia may need, but not want, someone to explain the form or document to them.

Finally, this study likely overestimates the American patient’s HL. Illiteracy still carries a significant stigma. Individuals are aware of this stigma and many individuals will not admit to any level of illiteracy. Given the consequences of acknowledging illiteracy, it is reasonable to conclude these individuals would not participate in any population research or sit for lengthy literacy tests. This population self-selecting out of literacy tests likely results in an artificially higher average literacy level. In this study, we opted to utilize previously-reported mean literacy levels (eighth or ninth grade levels) as a proxy for HL,25–27 with the understanding that HL levels would be lower than literacy due to the specialized terminology. This results in HL proxy values likely being higher than expected in society. This again emphasizes the importance of documents being written in plain language to increase accessibility.

Limitations

There are a few potential variables and explanations for our findings, as well as some limitations to the generalizability of our results. First, because we only examined standardized forms, we cannot assume that the results represent an organization’s overall approach to HL for its patients. It is possible that the organizations we examined have focused their HL energy on other patient-facing items, like discharge summaries or medication documentation, versus the more “transactional” ROI and other HI forms, so these results might not be representative of an organization’s overall awareness or implementation of HL efforts.

By limiting our sample to those healthcare systems considered “top” by a Newsweek article, we have left open the possibility that those not in this tranche may be even more mindful when creating the authorization forms, especially if they serve different populations, so the results cannot be extrapolated to the entire industry. Our study was also limited to two readability scales out of the many available tests discussed earlier in this paper. It is possible that the forms we examined would have been rated within the standard parameters on other readability scales.

Future Research

We recommend that future research evaluate the presence of language-specific authorizations in various parts of the United States. For example, we would expect that cities or areas with large populations of foreign language-speaking patients would have authorization form options that match the various significant foreign languages represented. Researchers could determine what percentage of foreign language-speaking potential patients live in a certain area and compare literacy in the various translated authorizations for health systems that service those areas.

Another suggestion for future research would be to have HI professionals propose their ideal design of the authorization form (eg, order of sections based on measurable studies of the variables. HI professionals have long advocated for patient access to their PHI while simultaneously ensuring that patients are informed about their privacy rights. With the focus on patient access, it is important to ensure that patients can obtain the specific information they want and they can utilize that information. If we have a HI-designed form, we can utilize user experience professionals to test the effectiveness and readability of that design and its effect on patients’ HL. Specific research could look at the patient preferences in forms (eg, two pages vs three or more pages to provide more room), assess whether a widget on an organization’s website to translate the authorization would be used and trusted by patients, and trial other non-intrusive measures to accommodate specific populations without calling attention to a patient’s difference.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from our three phases of research involving authorization forms provide insight into how HL can be important for HI professionals. The results from the third analysis, in which we evaluated the readability levels of forms utilized by large requestor agencies, showed that it is possible to achieve an authorization form that meets the plain language requirements. The readability results from forms used by healthcare provider organizations lag those of the third-party requesters and could be improved to support patient success and outcomes. HI professionals should take this opportunity to improve their organizations’ patient-facing forms. These efforts should be conducted systematically so that there is confidence in the results.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this research.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Appendix

Appendix 1.Study 1 Sample with the top 150 Hospitals Listed in a 2023 Newsweek Report and the websites for the Release of Information forms.

Bibliography

-

1.

Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social Determinants of Health Equity.

Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S4):S517-S519. doi:

10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200

-

2.

Gottlieb L, Fichtenberg C, Alderwick H, Adler N. Social Determinants of Health: What’s a Healthcare System to Do?

J Healthc Manag. 2019;64(4):243-257. doi:

10.1097/JHM-D-18-00160

-

-

4.

DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature.

J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228-1239. doi:

10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x

-

5.

Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease.

Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):267-275. doi:

10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00239-2

-

6.

Berkman ND, Pignone MP, DeWalt DA, Sheridan S. Health Literacy: Impact on Health Outcomes. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004.

-

7.

Kaphingst KA, Weaver NL, Wray RJ, Brown ML, Buskirk T, Kreuter MW. Effects of patient health literacy, patient engagement and a system-level health literacy attribute on patient-reported outcomes: a representative statewide survey.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):475. doi:

10.1186/1472-6963-14-475

-

8.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Evidence Does Not Support Clinical Screening of Literacy.

J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(1):100-102. doi:

10.1007/s11606-007-0447-2

-

9.

Committee on Health Literacy, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine.

Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. (Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds.). National Academies Press; 2004:10883. doi:

10.17226/10883

-

10.

Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association.

JAMA. 1999;281(6):552-557. doi:

10.1001/jama.281.6.552

-

11.

Neter E, Brainin E. Association Between Health Literacy, eHealth Literacy, and Health Outcomes Among Patients With Long-Term Conditions: A Systematic Review.

Eur Psychol. 2019;24(1):68-81. doi:

10.1027/1016-9040/a000350

-

12.

Jenson BB, Currie C, Dyson A, Eisenstadt N, Melhuish E. Early Years, Family and Education Task Group: Report, European Review of Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide in the WHO European Region. World Health Organization; 2013.

-

13.

Al Sayah F, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA. Association of Inadequate Health Literacy with Health Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Depression: Secondary Analysis of a Controlled Trial.

Can J Diabetes. 2015;39(4):259-265. doi:

10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.11.005

-

14.

Bailey SC, Brega AG, Crutchfield TM, et al. Update on Health Literacy and Diabetes.

Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(5):581-604. doi:

10.1177/0145721714540220

-

15.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review.

Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97. doi:

10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

-

16.

Leonard Grabeel K, Russomanno J, Oelschlegel S, Tester E, Heidel RE. Computerized versus hand-scored health literacy tools: a comparison of Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) and Flesch-Kincaid in printed patient education materials.

J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(1). doi:

10.5195/jmla.2018.262

-

17.

Wang MJ, Lo YT. Improving Patient Health Literacy in Hospitals – A Challenge for Hospital Health Education Programs.

Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:4415-4424. doi:

10.2147/RMHP.S332220

-

18.

Karagözoğlu M, İlhan N. The effect of health literacy on health behaviors in a sample of Turkish adolescents.

J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;77:e187-e194. doi:

10.1016/j.pedn.2024.04.028

-

19.

Dell CA, Harrold B, Dell T. Test Review: Wilkinson, G. S., & Robertson, G. J. (2006). Wide Range Achievement Test—Fourth Edition. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. WRAT4 Introductory Kit (includes manual, 25 test/response forms [blue and green], and accompanying test materials): $243.00.

Rehabil Couns Bull. 2008;52(1):57-60. doi:

10.1177/0034355208320076

-

20.

Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ.

Wide Range Achievement Test—Fourth Edition. 4th ed. Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. doi:

10.1037/t27160-000

-

21.

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391-395.

-

22.

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: A new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills.

J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537-541. doi:

10.1007/BF02640361

-

23.

Weiss PA, Vivian JE, Weiss WU, Davis RD, Rostow CD. The MMPI-2 L Scale, reporting uncommon virtue, and predicting police performance.

Psychol Serv. 2013;10(1):123-130. doi:

10.1037/a0029062

-

24.

Voigt-Barbarowicz M, Brütt AL. The Agreement between Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Assessment of Patients’ Health Literacy—A Systematic Review.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2372. doi:

10.3390/ijerph17072372

-

25.

Barclay PA, Bowers CA. Design for the Illiterate: A Scoping Review of Tools for Improving the Health Literacy of Electronic Health Resources.

Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 2017;61(1):545-549. doi:

10.1177/1541931213601620

-

-

-

-

29.

Delaney FT, Doinn TÓ, Broderick JM, Stanley E. Readability of patient education materials related to radiation safety: What are the implications for patient-centred radiology care?

Insights Imaging. 2021;12(1):148. doi:

10.1186/s13244-021-01094-3

-

30.

Flesch R. A new readability yardstick.

J Appl Psychol. 1948;32(3):221-233. doi:

10.1037/h0057532

-

-

32.

Kiselnikov A, Vakhitova D, Kazymova T. Fundamentals of materials (text readability evaluation). Vdovin E, ed.

E3S Web Conf. 2021;274:12006. doi:

10.1051/e3sconf/202127412006

-

33.

Walters KA, Hamrell MR. Consent forms, lower reading levels, and using Flesch-Kincaid readability software.

Drug Inf J. 2008;42(4):385-394. doi:

10.1177/009286150804200411

-

34.

Johnston J, Giles M. Still Flumoxed by the Flesch Kincaid Score?: Readability and Plain English in Surgical Patient Information Leaflets.

Int J Surg. 2017;47:S55. doi:

10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.08.285

-

35.

Choudhry AJ, Baghdadi YMK, Wagie AE, et al. Readability of discharge summaries: with what level of information are we dismissing our patients?

Am J Surg. 2016;211(3):631-636. doi:

10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.12.005

-

-

-

-

39.

Farach N, Faba G, Julian S, et al. Stories From the Field: The Use of Information and Communication Technologies to Address the Health Needs of Underserved Populations in Latin America and the Caribbean.

JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;1(1):e1. doi:

10.2196/publichealth.4108

-

-

41.

Miller TA. Health literacy and adherence to medical treatment in chronic and acute illness: A meta-analysis.

Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(7):1079-1086. doi:

10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.020

-

42.

Hibbard JH, Greene J. What The Evidence Shows About Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes And Care Experiences; Fewer Data On Costs.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-214. doi:

10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061

-

43.

Grosjean F, Li P. The Psycholinguistics of Bilingualism.

-

44.

Joshi A, Mohan SK, Pandya AK, et al. Improving the Health and Well-Being of Individuals by Addressing Social, Economic, and Health Inequities (Healthy Eating Active Living): Protocol for a Cohort Study.

JMIR Res Protoc. 2025;14:e41169. doi:

10.2196/41169

-

45.

Sharma S, Latif Z, Makuvire TT, et al. Readability and Accessibility of Patient-Education Materials for Heart Failure in the United States.

J Card Fail. 2025;31(1):154-157. doi:

10.1016/j.cardfail.2024.06.015