Download PDF

Abstract

Background

The need for interprofessional education (IPE) in the health professions has been recognized for many years with the intent to move related health disciplines toward more collaborative efforts.

Methods

This explanatory sequential mixed methods study evaluated IPE readiness in Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) and Health Information Management (HIM) students at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette before and after an introductory IPE workshop titled “IPE is Key.” Of the total 1,003 BSN and HIM students, 109 voluntarily participated in the workshop, with 78 completing the pre- and post-assessment for a response rate of 71.6% of attendees and 7.8% of all BSN and HIM students who fit the inclusion criteria.

Results

Analysis of pre- and post-workshop assessment scores revealed a statistically-significant increase in IPE readiness of participants (p<0.001). Findings support the implementation of an annual introductory workshop for early BSN and HIM students, with potential expansion to other health professions. Findings of the study were utilized to develop the “IPE is Key” Instructor’s Guide, which provides educators the necessary information to deliver engaging IPE activities shown to enhance students’ readiness to learn collaboratively.

Conclusions

This study’s findings highlight the need for an annual introductory IPE workshop for early BSN and HIM learners, with the potential to include other health related professions students at UL Lafayette. The findings also suggest that the introductory workshop may improve readiness for and satisfaction with the Fall-semester IPHE 310 interprofessional academic course, which includes BSN and HIM students.

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization,1 interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) involves healthcare professionals from various disciplines working together with patients, families, and communities to provide the highest quality care. In this model, healthcare teams share expertise while delivering care.2,3 IPCP thrives on teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking among healthcare professionals. Research emphasizes that training for IPCP should begin early in healthcare education, highlighting the role of interprofessional education (IPE) in acquiring the knowledge and skills needed to collaborate effectively.4,5

A major player in IPCP and IPE, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC), was formed in 2009 as a partnership of six national education associations aimed at advancing interprofessional learning experiences to help students prepare for team-based care in the professional arena.6 IPEC continues to engage multiple health professions in its efforts to guide curriculum development across health professions schools.

Accrediting bodies for healthcare education programs recognize the importance of IPE and mandate its inclusion in curricula. The Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative promotes interprofessional teams that deliver high-quality, cost-effective care, making it essential to train students in teamwork and collaboration to prepare them for the workforce.7 Research has demonstrated that IPE improves teamwork, collaboration, and understanding of professional roles, thereby enhancing healthcare delivery.8–12 As a result, IPE has expanded significantly in health professional programs over the past decade, with 92% of medical schools now incorporating it into their curricula.6

Health professions students benefit from various IPE formats, including one-day workshops, a series of activities, or semester-long courses.4,5,13 Many studies have reported positive outcomes from IPE interventions,12,14,15 though only limited research has explored IPE between clinical students (such as those in medicine and nursing) and non-clinical students (such as those in health information management [HIM]), particularly regarding their readiness for IPE.8 At the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (UL Lafayette), leaders in the BSN and HIM programs sought to prepare students for collaborative practice through a junior level interprofessional nursing and HIM course, IPHE 310: Professional Values, Ethical and Legal Tenets of Healthcare. Despite multiple course revisions, student evaluations of the course consistently indicated students’ lack of understanding and appreciation of the value of IPE for their future roles on healthcare teams. Student feedback highlighted gaps in knowledge and appreciation of the professional roles of other disciplines. Faculty theorized this disconnect may stem from the clinical focus of nursing versus the non-clinical, indirect patient care roles of HIM professionals, potentially leading to misunderstandings about how each profession contributes to improving patient care and health outcomes.

The purpose of this study was to examine the attitudes and readiness of BSN and HIM students at the UL Lafayette regarding IPE before and after attending an educational workshop called “IPE is Key.” Additionally, the experiences and perceptions of two BSN and HIM student groups concerning IPE and IPCP were explored. In this two-phase, explanatory sequential mixed-methods study, qualitative insights explained, enriched, and clarified the quantitative results. In the first phase of the study, pre- and post-assessments were administered electronically, while qualitative data were collected through two semi-structured focus groups. This paper presents the quantitative findings from the larger mixed methods study.

METHODS

The potential study participants included 1,003 undergraduate students from the BSN and HIM programs at UL Lafayette. Convenience sampling was employed, as the participants were students who voluntarily attended the “IPE is Key” workshop. Of the 109 students who attended the workshop, 78 (71.6% of attendees; 7.8% of all potential students) submitted pre- and post-workshop assessments, which confirmed their consent to participate in the study.

The workshop invitation was disseminated through various channels, including email, faculty announcements in class, postings in the learning management system, and physical bulletin boards in main corridors. Once registration was closed, the registrants were grouped into teams of five, which included a diverse blend of students from different disciplines, ranks, and previous completion of the IPHE 310 course.

Students who participated in the “IPE is Key” workshop were asked to complete pre- and post-workshop assessments to measure changes in their attitudes and readiness for IPE. These assessments were adapted with permission from a previously validated IPE readiness tool, the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale.16

Intervention

The “IPE is Key” workshop was developed in alignment with adult learning principles, which emphasize that adult learners are motivated internally, ready to learn, and need to understand the value of what they are being taught.17 Although some participants had previously completed the junior-level course IPHE 310: Professional Values, Ethical and Legal Tenets of Healthcare, they had not yet been introduced to key concepts of IPE, such as its significance, core competencies, and role in team-based care. For other students, the workshop provided their first formal exposure to IPE during their undergraduate education. Because of the diverse nature of participants, the workshop was designed using the Kirkpatrick Model of Learning Outcomes18 and targeted students at the foundational stage of their education, as defined by the Interprofessional Learning Continuum (IPLC).19 However, since some participants were in their junior and senior years, they had potential to offer insights on whether an earlier IPE intervention would have been beneficial.

The learning objectives of the “IPE is Key” workshop focused on several key areas. Participants were expected to discuss the history and purpose of IPC and IPE, while also identifying and explaining their roles within a healthcare team. They were encouraged to recognize and utilize effective communication strategies essential for team collaboration and to demonstrate respect and understanding for the beliefs and values that distinguish specific health professions from others. Additionally, students were tasked with identifying both the similarities and differences in the roles and scopes of each discipline involved in the workshop.

“IPE is Key” Workshop Activities

Each group of students was assigned a facilitator (faculty or staff member) from either discipline. After the welcome message and the pre-workshop assessment, a short introductory slide presentation was shown, which highlighted learning objectives along with an overview of the definition and history of IPE, the IPEC core competencies, and the benefits of IPE for both healthcare professionals and patients. Research highlighting IPE’s role in facilitating improved patient outcomes was integrated throughout the workshop, illustrating the evidence-based nature of IPE.

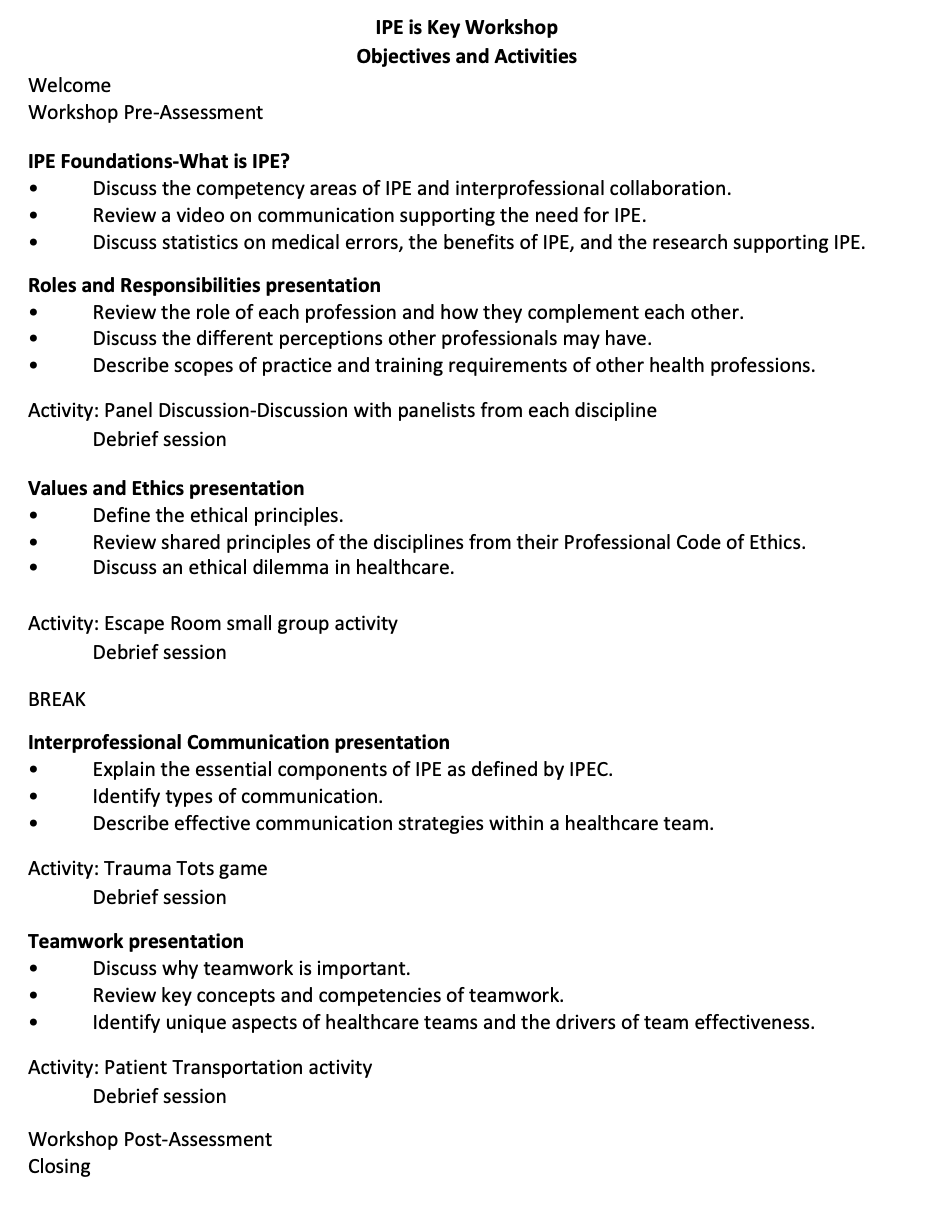

Each activity in the workshop was related to a core competency of IPE: teamwork, communication, values and ethics, and roles and responsibilities. Each activity also contained specific learning objectives and included a brief presentation given by a faculty member from HIM or BSN (Figure 1). The first activity, covering the IPE core competency of roles and responsibilities, featured professionals from both BSN and HIM programs sharing insights on how various disciplines have influenced their careers and patient care. The panel participants also explored potential interactions between nursing and HIM in professional healthcare settings.

Figure 1.“IPE is Key” Workshop Objectives and Activities

Following a review of the values and ethics associated with each profession, students engaged in an escape room-style activity. In this exercise, they worked collaboratively to solve problems, riddles, or questions related to professional values and ethics to advance to the next level. Each level was designed to align with the professional code of ethics of each profession, identify the similarities between the two codes, and encourage students to work as a team. The first team to successfully complete the escape room was the winner.

Students then participated in a team-building exercise where they simulated guiding a patient through the hospital to the correct department while avoiding potential safety errors. In this exercise, teams collaborated to ensure the safe navigation of their “patient” (represented by a ball) placed on a tarp (representing the “hospital”) with holes labeled as the various departments or rooms. The patient started in the area labeled the emergency room and traveled to an assigned room in the hospital. The team that safely navigated the patient to the correct area with no safety errors (ball falling into the wrong hole) won the competition.

After a brief review of communication skills essential for effective healthcare teamwork, students participated in a final activity designed to reinforce and apply these communication skills within a team setting. The activity involved a Mr. Potato Head™ toy, which represented a trauma victim. The purpose was to put the patient back together exactly how they looked prior to the accident. A photo of a completed Mr. Potato Head™ toy was given to one participant in each group, who was then instructed to go into a different room. No other team members were allowed to see the photo at any point in the game. Each team then selected the “transporter” who relayed information from the student with the picture back to the rest of the group. The organ bank harvesters then selected the appropriate piece (as described by the transporter) from a bucket of ears, eyes, nose, hats, glasses, arms and legs. The first team to correctly reconstruct Mr. Potato Head™ patient prevailed. After each of the activities, a discussion was held to discuss the value of the activity in promoting collaboration. A facilitator observed and encouraged discussion.

Data Collection

Data collection included pre- and post-workshop assessments in which students were asked to indicate whether they had completed the Fall semester, junior-level IPHE 310 course and to rate their level of agreement with statements adapted from the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS).16 Originally developed by Parsell and Bligh, the RIPLS is widely used to evaluate students’ attitudes toward and readiness for IPC and IPE.19–22 The 2005 revised version of the RIPLS consists of 19 items measured on a five-point Likert scale, divided into four subscales: Teamwork/Collaboration, Positive Professional Identify, Negative Professional Identity, and Roles and Responsibilities.23 Higher scores indicate greater readiness for IPE, with a maximum score of 95 (Table 1).

Table 1.Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale[@415118] Categories and Statements

| Teamwork and Collaboration |

- Learning with other students will help me become a more effective member of a healthcare team.

|

- Patients would ultimately benefit if health professions students worked together.

|

- Shared learning with other health professions students will increase my ability to understand clinical problems.

|

- Learning between health professions students before graduation would improve working relationships after graduation.

|

- Communication skills should be learned with other health professions students.

|

- Shared learning will help me think positively about other health professionals.

|

- For small-group learning to work, students need to respect and trust each other.

|

- Team-working skills are vital for all health professions students to learn.

|

- Shared learning will help me to understand my own professional limitations.

|

| Negative Professional Identity |

- I don't want to waste time learning with other health professions students.

|

- It is not necessary for undergraduate health professions students to learn together.

|

- Clinical problem-solving can only be learned effectively with students from my own school.

|

| Positive Professional Identity |

- Shared learning with other health professionals will help me to communicate better with patients and other professionals.

|

- I would welcome the opportunity to work on small group projects with other health professions students.

|

- Shared learning will help clarify the nature of patients' and clients' problems.

|

- Shared learning before graduation will help me become a better team worker.

|

| Roles and Responsibilities |

- The function of nurses and HIM professionals is mainly to provide support for doctors.

|

- I am not sure what my professional role will be.

|

- I have to acquire much more knowledge and skill than other health professions students.

|

Adapted with permission from McFadyen et al. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2005; 19(6): 595–603.[@415125]

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata v18.0 software. Descriptive statistics were applied to evaluate demographic information, while paired sample t-tests were conducted to assess whether post-assessment scores showed a statistically significant increase over pre-assessment scores, with significance set at p≤.05.

RESULTS

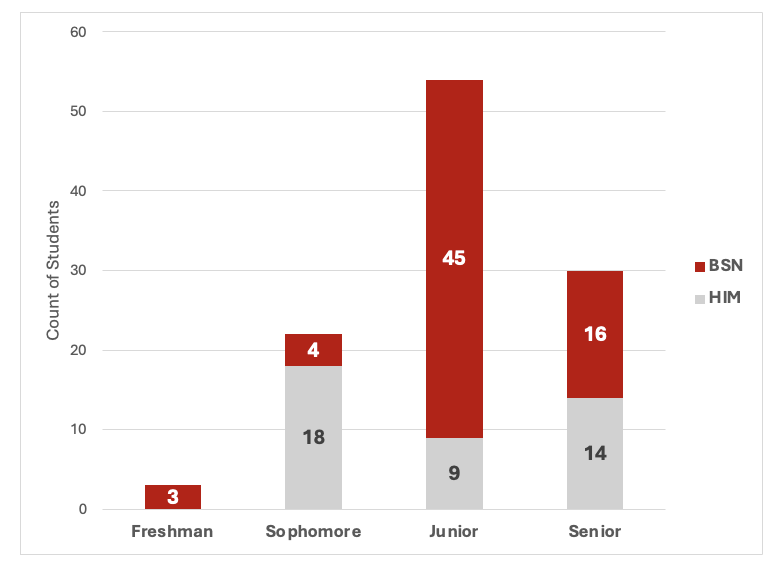

Of the 109 students who participated in the workshop, 68 nursing students (62.4%) and 41 HIM students (37.6%) were in attendance. Of the attendees, 30 were seniors (27.5%; 16 BSN majors [53.3%] and 14 HIM majors [46.7%]). The largest percentage, nearly half, were juniors (54; 49.5%), with the largest percentage of juniors belonging to the BSN program (45; 83.3%). Another 20.2% (22) were sophomores, of which most (18; 81.8%) were HIM students, and few (3; 2.8%) were freshmen, exclusively from the HIM program. Figure 2 shows the academic level distribution among both groups.

Figure 2.“IPE is Key” Workshop Attendees by Major and Academic Level.

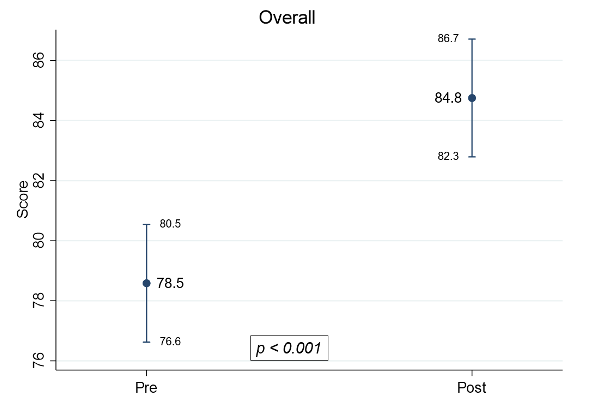

Participants’ IPE readiness increased from M=78.5 (pre) to M=84.8 (post) with a mean difference of 6.3 (Figure 3). A paired sample t-test comparison of the overall pre- and post-assessment data indicated a statistically-significant improvement in students’ readiness scores (p<0.001). This significant difference, alongside the increase in mean scores, suggests that the “IPE is Key” workshop positively impacted students’ attitudes and readiness to engage in interprofessional learning. These findings align with previous studies that demonstrate enhanced student readiness for IPE following an introductory educational intervention.5,10,24–26 These phase one quantitative results enabled us to address the research question, “Is there a significant difference in UL Lafayette BSN and HIM students’ attitudes and readiness for IPE before and after the “IPE is Key” workshop?”

Figure 3.Mean Scores of Overall Pre- and Post-Intervention Assessments

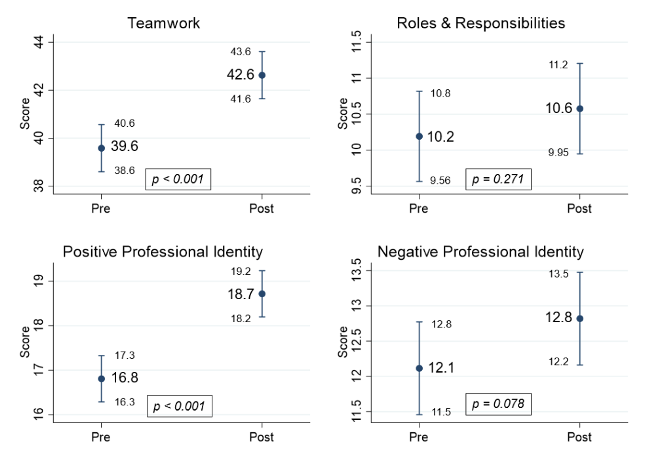

The pre- and post-assessment scores for the four RIPLS categories—teamwork and collaboration, positive professional identity, negative professional identity, and roles and responsibilities—were analyzed and stratified (Figure 4). In the category of teamwork and collaboration, the mean pre-assessment score increased from 39.6 to 42.6 post-assessment, with paired sample t-tests revealing a statistically significant difference (p<0.001). This significant increase suggests an improvement in students’ attitudes and readiness for collaborative learning and respect for other health professions. Similarly, in the category of positive professional identity, the mean score rose from 16.8 pre-assessment to 18.7 post-assessment, also showing a statistically significant difference (p<0.001). This suggests enhanced readiness and attitudes toward developing a positive professional identity following the “IPE is Key” workshop. These positive outcomes in the teamwork and collaboration and positive professional identity categories are consistent with findings from previous studies, which also reported improvements in these areas.5,25

Figure 4.Results of Pre- and Post-assessment Scores Analysis by Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale16 Categories

The RIPLS categories of positive and negative professional identity assess students’ perceived benefits and value derived from collaborating with peers in other health professions.21 There was no significant increase in the mean pre-assessment score for negative professional identity, which was 12.1, compared with a post-assessment score of 12.8 (p = 0.078). The negatively worded statements in the negative professional identity and roles and responsibilities categories may have contributed to confusion among students.22 Similarly, the comparison of pre- and post-scores in the roles and responsibilities category showed no significant increase, with mean scores of 10.2 pre-assessment and 10.6 post-assessment (p = 0.271), which aligns with other research27 that also found no significant change in the roles and responsibilities category in pre- and post-assessments. Rossler and Kimble postulated that because roles and responsibilities vary for the different health professions, this may be related to the low internal consistency reliability of this subscale.27

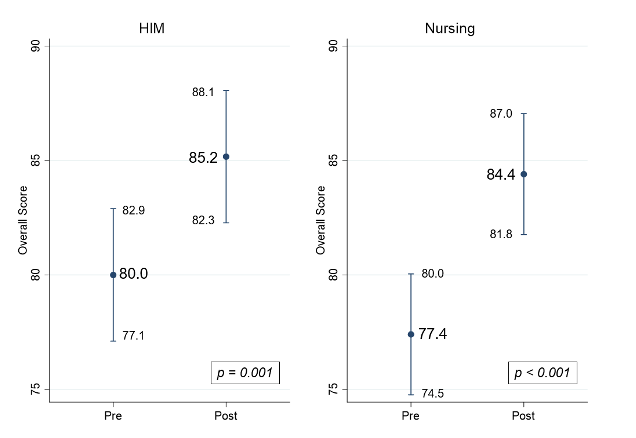

The pre- and post-assessment scores were also analyzed by participants’ major (Figure 5). HIM students’ scores increased from 80.0 to 85.2, with a mean difference of 5.2 (p = 0.001). BSN students’ scores rose from 77.4 to 84.4, with a mean difference of 7.0 (p < 0.001). Students from both majors showed significant improvement, indicating that participants benefited from the “IPE is Key” workshop.

Figure 5.Results of Pre- and Post-assessment Scores Analysis by Academic Major

Pre- and post-assessment scores were also analyzed based on whether students had completed the IPHE 310 course. For those who hadn’t, scores increased from 79.2 to 84.7, with a mean difference of 5.5 (p < 0.001). Scores of students who had completed the course increased from 78.0 to 84.8, with a mean difference of 6.8 (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in readiness between students who had completed the course and those who had not.

DISCUSSION

The quantitative findings of this study demonstrated a significant increase in the readiness for IPE among participants following the “IPE is Key” workshop. Notably, the scores in the subcategories of teamwork and collaboration, as well as positive professional identity, showed substantial improvements. These results indicate improved attitudes toward collaborative learning, the development of a positive professional identity, and greater respect for other health professions after the workshop. When examining overall scores by academic major and prior completion of the fall semester IPHE 310 course, no significant differences were found between the groups. However, it is noteworthy that the pre-workshop scores of students who had completed the course were lower than those of their peers who had not. This may reflect the unfavorable evaluation results noted previously, suggesting a need for further examination of the course and investigation to clarify this outcome. Analysis of IPE readiness scores stratified by students’ year in their respective programs or evidence of previous interprofessional collaboration in the healthcare setting was not included in this study but should be considered for future research.

However, the workshop’s success—evident from the increased readiness scores—motivated the lead author to create a resource for faculty and staff in health programs interested in implementing an introductory IPE workshop for early learners. The “IPE is Key” Instructor’s Guide (Figure 6) offers educators the necessary information to deliver engaging IPE activities that have been shown to enhance students’ readiness to learn collaboratively.

Figure 6.Interprofessional Education Instructor’s Guide, Manual Content Outline

Interprofessionalism Impact

Given the significance of IPE and IPC in healthcare, interprofessionalism forms the foundation of this study. The “IPE is Key” workshop was created to familiarize BSN and HIM students with IPE and various healthcare professions. Faculty and staff from these departments collaborated interprofessionally to organize and deliver the workshop. Sixteen faculty and staff from the departments came together to present or volunteer as facilitators. Future plans for IPE at the UL Lafayette may involve including students from other health-related programs in the “IPE is Key” workshop, as well as developing additional IPE activities, simulations, or courses.

CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this study was to assess the attitudes and readiness for IPE among BSN and HIM students at UL Lafayette before and after their participation in the “IPE is Key” workshop. The results revealed a statistically-significant increase in mean scores, suggesting an improvement in students’ attitudes and readiness for IPE following the workshop. Participants expressed appreciation for interactions with peers from other health professions and a desire for more such opportunities.

Research has demonstrated that IPE enhances the collaboration and teamwork skills of health profession students.20,28,29 Readiness for IPE is fundamental for IPE success, and it is vital for academic institutions to continue offering effective IPE experiences to help students develop collaborative skills that will carry into their professional careers, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors received an internal faculty grant from the Student Center for Research, Creativity, & Scholarship (SCRCS) at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in the amount of $5,000.

Bibliography

-

-

2.

Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, Collaboration, Coordination, and Networking: Why We Need to Distinguish Between Different Types of Interprofessional Practice.

Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2018;32(1):1-3. doi:

10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150

-

3.

Schot E, Tummers L, Noordegraaf M. Working on Working Together: A Systematic Review on How Healthcare Professionals Contribute to Interprofessional Collaboration.

Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2020;34(3):332-342. doi:

10.1080/13561820.2019.1636007

-

4.

Brisolara KF, Culbertson R, Levitzky E, Mercante DE, Smith DG, Gunaldo TP. Supporting Health System Transformation: The Development of an Integrated Interprofessional Curriculum Inclusive of Public Health Students.

Journal of Health Administration Education. 2019;36(1):111-121.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6959473/

-

5.

Moote R, Anthony C, Ford L, Johnson L, Zorek J. A Co-Curricular Interprofessional Education Activity to Facilitate Socialization and Meaningful Student Engagement.

Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2021;13(12):1710-1717. doi:

10.1016/j.cptl.2021.09.044

-

-

-

8.

Anderson OS, August EL, Goldberg PK, Youatt E, Beck AJ. Developing a Framework for Population Health in Interprofessional Training: An Interprofessional Education Module.

Frontiers in Public Health. 2019;7:58. doi:

10.3389/fpubh.2019.00058

-

9.

Homeyer S, Hoffmann W, Hingst P, Oppermann RF, Dreier-Wolfgramm A. Effects of Interprofessional Education for Medical and Nursing Students: Enablers, Barriers and Expectations for Optimizing Future Interprofessional Collaboration – A Qualitative Study.

BMC Nursing. 2018;17(1):13. doi:

10.1186/s12912-018-0279-x

-

10.

Kim YJ, Radloff JC, Stokes CK, Lysaght CR. Interprofessional Education for Health Science Students’ Attitudes and Readiness to Work Interprofessionally: A Prospective Cohort Study.

Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy. Published online 2018:1-9. doi:

10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.09.003

-

-

12.

Madigosky WS, Franson KL, Glover JJ, Earnest M. Interprofessional Education and Development (IPED): A Longitudinal Team-Based Learning Course Introducing Teamwork/Collaboration, Values/Ethics, and Safety/Quality to Health Professional Students.

Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice. 2018;16(1):1-5. doi:

10.1016/j.xjep.2018.12.001

-

13.

Witt Sherman D, Flowers M, Rodriguez Alfano A, et al. An Integrative Review of Interprofessional Collaboration in Health Care: Building the Case for University Support and Resources and Faculty Engagement.

Healthcare. 2020;8(4). doi:

10.3390/healthcare8040418

-

14.

Bond BM, Dehan J, Horacek M. Does Interprofessional Interaction Influence Physical Therapy Students’ Attitudes Toward Chiropractic?

Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2018;62(3):143-148.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30662068/

-

15.

Derouin A, Holtschneider ME, McDaniel KE, Sanders KA, McNeill DB. Let’s Work Together: Interprofessional Training of Health Professionals in North Carolina.

North Carolina Medical Journal. 2018;79(4):223-225. doi:

10.18043/ncm.79.4.223

-

16.

Parsell G, Bligh J. The Development of a Questionnaire to Assess the Readiness of Healthcare Students for Interprofessional Learning.

Medical Education. 1999;33(2):95-100. doi:

10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x

-

17.

Knowles MS. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. Revised. Cambridge Adult Education; 1980.

-

18.

Doll J, Breitback A, Eliot K. Models of Delivery. In: Hamson-Utley J, Mathena CK, Gunaldo TP, eds. Interprofessional Education and Collaboration: An Evidence-Based Approach to Optimizing Health Care. Human Kinetics; 2021:17-38.

-

19.

Institute of Medicine.

Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes. National Academies Press; 2015. doi:

10.17226/21726

-

20.

Alruwaili A, Mumenah N, Alharthy N, Othman F. Students’ Readiness for and Perception of Interprofessional Learning: A Cross-Sectional Study.

BMC Medical Education. 2020;20(1):390. doi:

10.1186/s12909-020-02325-9

-

21.

Binienda J. Critical Synthesis Package: Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS).

MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10274. doi:

10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10274

-

22.

Roopnarine R, Boeren E. Applying the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) to Medical, Veterinary and Dual Degree Master of Public Health (MPH) Students at a Private Medical Institution.

PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234462. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0234462

-

23.

McFadyen AK, Webster V, Strachan K, Figgins E, Brown H, McKechnie J. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale: A Possible More Stable Sub-Scale Model for the Original Version of RIPLS.

Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005;19(6):595-603. doi:

10.1080/13561820500430157

-

24.

Murray M. The Impact of Interprofessional Simulation on Readiness for Interprofessional Learning in Health Professions Students.

Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2021;16(3):199-204. doi:

10.1016/j.teln.2021.03.004

-

25.

Nguyen HTT, Wens J, Tsakitzidis G, et al. A Study of the Impact of an Interprofessional Education Module in Vietnam on Students’ Readiness and Competencies.

PLOS ONE. 2024;19(2):e0296759. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0296759

-

26.

Numasawa M, Nawa N, Funakoshi Y, et al. A Mixed Methods Study on the Readiness of Dental, Medical, and Nursing Students for Interprofessional Learning.

PLOS ONE. 2021;16(7):e0255086. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0255086

-

27.

Rossler KL, Kimble LP. Capturing Readiness to Learn and Collaboration as Explored with an Interprofessional Simulation Scenario: A Mixed-Methods Research Study.

Nurse Education Today. 2016;36:348-353. doi:

10.1016/j.nedt.2015.08.018

-

28.

Guraya SY, Barr H. The Effectiveness of Interprofessional Education in Healthcare: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018;34(3):160-165. doi:

10.1016/j.kjms.2017.12.009

-

29.

Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, et al. The Effectiveness of Interprofessional Education: Key Findings from a New Systematic Review.

Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2010;24(3):230-241. doi:

10.3109/13561820903163405