Download PDF

CE Quiz

Abstract

Background

In electronic health records (EHRs), standardization and interoperability challenges stem from fragmented data across institutions. Federated learning, a distributed machine learning framework through which multiple institutions can collaborate on model development while maintaining patient data privacy, bridges this gap by training shared models while keeping data localized. Therefore, this study focused on the application of federated learning in the biomedical domain, with the aim of addressing statistical challenges, system complexities, and privacy issues.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, the authors conducted a comprehensive literature search across PubMed/Medline, Cochrane/EMBASE, PEDro, SCOPUS, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Embase, and arxiv, covering publications from January 2020 to April 2024. The search included terms such as “electronic health records,” “EHR,” “electronic medical records,” “EMR,” “registry/registries,” “tabular,” “federated learning,” “distributed learning,” and “distributed algorithms.” Data were extracted on cohort characteristics, modeling approaches, and federated learning frameworks.

Results

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to 58 initial results, we analyzed 15 previously-published articles. According to the results described in those articles, federated learning improved data sharing and analysis in various healthcare environments, enhancing EHR standardization and interoperability. Federated learning models typically matched or surpassed localized models, especially when local data was limited or fragmented, and were particularly effective in predicting rare diseases and handling different data types. The use of federated averaging, personalized models, and heterogeneity-aware aggregation methods effectively managed diverse data, ensuring strong performance. Federated learning also maintained privacy and security by keeping patient data local and implementing advanced security protocols like differential privacy.

Conclusions

Federated learning represents a transformative advancement in health informatics, addressing the critical need for seamless data exchange in the fragmented US healthcare landscape. By improving patient outcomes and operational efficiencies, federated learning paves the way for leveraging big data analytics on a nationwide scale.

INTRODUCTION

In the intricate tapestry of modern healthcare, the harmonization of Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems through standardization and interoperability stands as a cornerstone for advancing health informatics. The pursuit of this harmonization is not merely a technical challenge; it is a transformative journey toward a future where healthcare delivery is seamless, patient-centered, and data-driven.1 The advent of federated learning heralds a new epoch in this journey, promising to bridge the chasms between disparate EHR systems and unlock the full potential of health informatics.2

The concept of federated learning is a beacon of innovation in the realm of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly within the healthcare sector. It is a distributed machine learning approach that enables multiple institutions to collaborate on model development without sharing sensitive patient data.3 This paradigm shift addresses the quintessential challenge of data privacy and security, which has long been a barrier to the aggregation and analysis of healthcare data. The integration of federated learning into EHR systems is not just an enhancement of existing processes; it is a redefinition of the very fabric of health data exchange and analysis.4

The fragmented nature of healthcare data, arising from myriad EHR systems with varying standards and protocols, has historically impeded the fluid exchange of information. This fragmentation is particularly pronounced in the United States, where the healthcare system is characterized by a diverse array of providers and systems. The lack of standardization and interoperability has resulted in siloed data repositories, hindering the ability to leverage this data for improved patient outcomes and operational efficiency.

Federated learning has emerged as one solution to these challenges, offering a pathway to standardization and interoperability that respects the sanctity of patient privacy.5 By enabling the collaborative training of AI models across multiple EHR systems while keeping the data localized, federated learning facilitates a level of data exchange and analysis previously unattainable.6

In the context of health informatics, the terms “AI,” “standardization,” and “interoperability” carry distinct meanings essential for understanding the challenges and contributions of federated learning. AI refers broadly to computational techniques, including machine learning and federated learning, which enables predictive modeling and decision-making in healthcare.7,8 Standardization, in this study, pertains to the harmonization of disparate EHR formats, enabling consistent data representation across institutions.9 Interoperability, closely linked to standardization, involves the seamless exchange and utilization of healthcare data, which federated learning facilitates by allowing collaborative model training while preserving data privacy.9,10

The implications of federated learning for health informatics are profound. It allows for the development of robust, generalizable AI models that can provide insights into patient care, disease progression, and treatment outcomes.11 These models, trained on diverse datasets from various institutions, can capture a more comprehensive picture of patient populations, leading to more accurate predictions and personalized care strategies.

Moreover, federated learning can accelerate the advancement of precision medicine. By harnessing the collective power of EHR data from multiple sources, researchers and clinicians can identify patterns and correlations that inform the development of targeted therapies and interventions.12 This collaborative approach to model development also fosters innovation, as it enables institutions to benefit from shared learnings while maintaining control over their data.

The journey towards standardization and interoperability in healthcare is fraught with challenges, both technical and regulatory.13 Federated learning, however, represents a convergence of technology and policy, where the technical capabilities of AI meet the regulatory requirements for data privacy and security.14 This convergence is essential for the realization of a healthcare system that is truly interconnected and patient-centric. As such, the impact of federated learning on EHR systems and health informatics also has broader implications for healthcare delivery. The standardization and interoperability enabled by federated learning have the potential to streamline clinical workflows, reduce redundancies, and eliminate errors. This paves the way for a healthcare ecosystem that is more responsive, resilient, and equipped to meet the challenges of an ever-evolving landscape. In this systematic review, we investigated the results of previous studies documenting the ways in which federated learning can be leveraged to overcome the challenges of standardization and interoperability within EHR systems, thereby enhancing health informatics.

METHODS

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure methodological rigor.15 We conducted our search across multiple databases, including PubMed, SCOPUS, Cochrane/EMBASE, PEDro, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Embase, and arXiv, covering studies published between 2020 and April 2024. A combination of keywords and Boolean operators was employed to identify relevant studies. The search terms included, but were not limited to, the following keywords: “Electronic Health Records,” “EHR,” “Electronic Medical Records,” “EMR,” “Registry/Registries,” “Tabular Data,” “Federated Learning,” “Distributed Learning,” and “Distributed Algorithms.” Thes search strategy, including Boolean operators and database-specific filters, was designed to comprehensively capture relevant studies across multiple databases. We then filtered the search results using language restrictions; only articles published in English were included in the study. No restrictions were applied to study design or geographic region to maximize inclusivity.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the review if they met specific criteria. Eligible studies addressed the application of federated learning in healthcare or biomedical domains. They also needed to focus on improving Electronic Health Record (EHR) interoperability and standardization and provide empirical data on federated learning models, including cohort characteristics, federated learning frameworks, modeling approaches, or comparative analyses with local models. Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals or reputable preprint archives, such as arXiv, were considered.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they did not focus on federated learning or its applications in healthcare. Results were also excluded if the article type was a review, editorial, or theoretical framework without empirical analysis. Studies published in languages other than English studies where the full text was unavailable via institutional subscription (“reports not retrieved”) or direct author contact, and studies where the methodological descriptions were incomplete were also excluded.

Eligibility Assessment

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by by three reviewers (first reviewer, KJ; second reviewer, NC; third reviewer, HB) for relevance of the study to federated learning and its applications in EHR systems. Full texts were then evaluated for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Specific attention was given to the methodological rigor of the studies, including detailed descriptions of datasets, modeling approaches, and performance metrics. Studies were also assessed for completeness of reported results and their alignment with the study’s objectives.

We extracted information from the selected publications in three categories:

-

data: cohort descriptive analysis, outcome, sample size per site and total, number of participating sites, data types, data public availability and number of features;

-

modeling: task and goal, modeling approach, hyperparameter methods, model performance metrics; and

-

federated learning framework: unit of federation, participating countries/regions, federated learning structure, federated learning topology, one-shot or not, evaluation metrics, convergence analysis, solution for heterogeneity, federated learning and local model comparison and code availability.

The results of our systematic review encompass data, modeling, federated learning frameworks, evidence of heterogeneity, comparative performance, and privacy and security to offer a comprehensive understanding of the influence of federated learning on EHR systems.

RESULTS

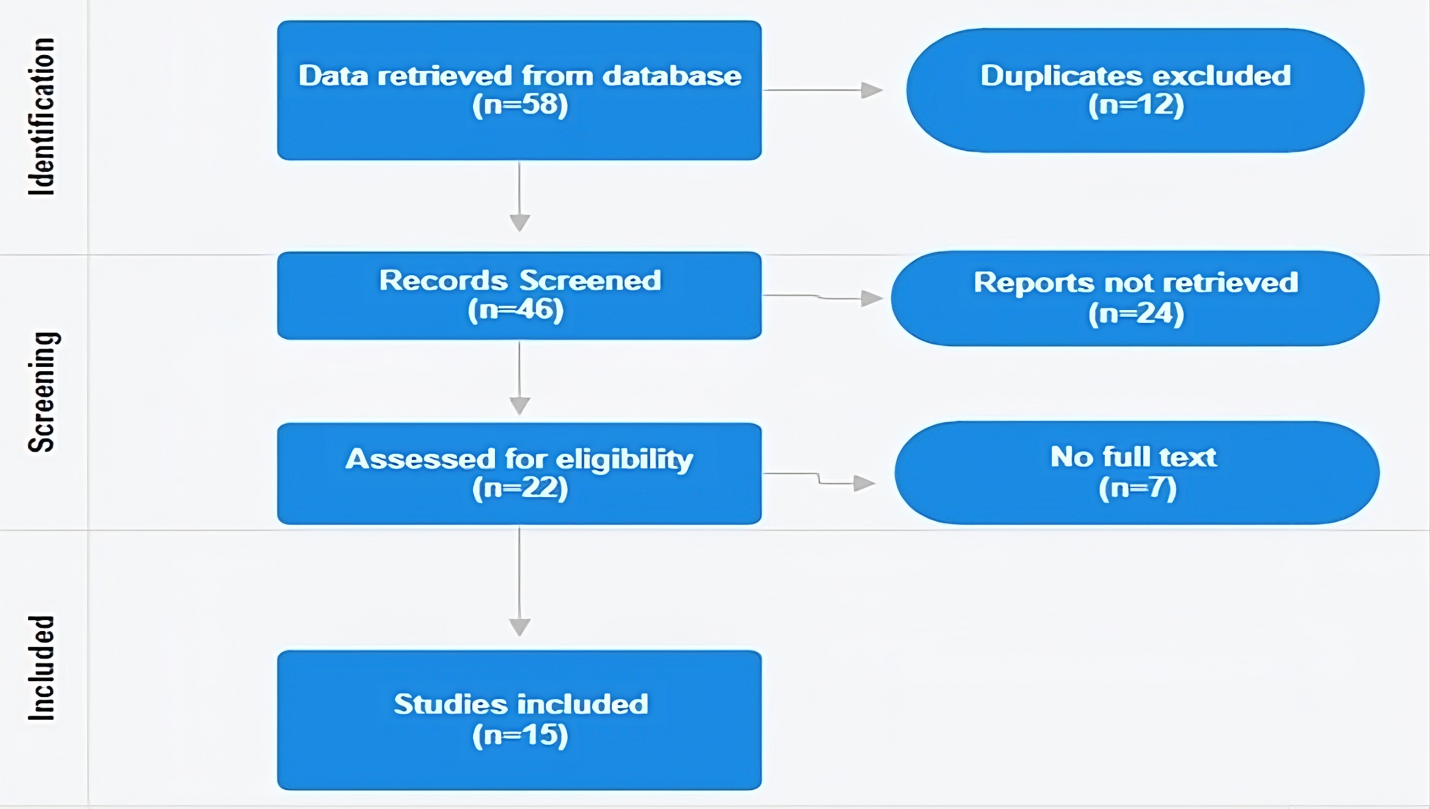

Our initial search yielded 58 total results. Of those, 12 were duplicates, 24 were not able to be retrieved, 7 did not have full text available, leaving us with 15 Ifor analysis in this review.1–3,5,6,13–22 Table 1 provides a summary of cohort sizes, the number of participating sites, and the number of features in the datasets across the reviewed studies.

Table 1.Summary of Findings: Federated Learning’s Role in Enhancing Standardization and Interoperability of EHR Systems

| Area of Analysis |

Key Findings Based on Reviewed Articles |

Supporting Citations |

| Data |

|

|

| Cohort Sizes |

Three studies reported cohort sizes ranging from a few hundred records to millions in large national registries, reflecting federated learning's capability to handle both small and large-scale data aggregation. |

Rajkomar et al[@421140]; McMahan et al[@421143]

Xu et al[@421162] |

| Outcome Measures |

Three studies reported that common outcomes analyzed in the literature included disease prevalence, treatment efficacy, patient outcomes, and predictive analytics, crucial for improving patient care and operational efficiencies. |

Albalawi et al[@421156]; Lopes et al[@421153];

Gadekallu et al[@421157] |

| Participating Sites |

Three studies reported that the number of participating sites in the studies ranged from 3 to over 100, demonstrating federated learning's scalability across multiple healthcare providers. |

Brisimi et al[@421152]; Antunes et al[@421139];

Kumar et al[@421158] |

| Data Types |

Three studies reported utilized tabular data from EHR systems, including demographics, clinical measurements, medication records, and diagnostic codes. |

Pollard et al[@421144]; Xu et al[@421162]; McMahan et al[@421143] |

| Data Public Availability |

Three studies reported provided public access to their datasets, highlighting the need for more open data initiatives to facilitate reproducibility and collaborative research. |

Dhiman et al[@421151]; Pollard et al[@421144]]; Jeon et al[@421147] |

| Number of Features |

Three studies reported that the number of features in datasets reported by studies ranged from a few dozen to several thousand, tailored to the complexity of the health outcomes under investigation. |

Gadekallu et al[@421157]; Amirahmadi et al[@421141];

Prayitno et al[@421163] |

| Modeling |

|

|

| Tasks and Goals |

Three studies reported addressing diverse modeling tasks including disease prediction, patient outcome forecasting, treatment pathway identification, and clinical workflow optimization. |

McMahan et al[@421143]; Albalawi et al[@421156]; Lopes et al[@421153] |

| Modeling Approaches |

Three studies reported employing a variety of machine learning models were employed in the literature, ranging from traditional statistical approaches to advanced neural networks and ensemble methods, with a focus on their adaptation to the distributed nature of Federated Learning. |

Prayitno et al[@421163]; Hur et al[@421150] |

| Hyperparameter Methods |

Two studies reported utilizing grid search and random search for hyperparameter optimization, with some studies leveraging Bayesian optimization for improved efficiency. |

Rauniyar et al[@421165]; Gadekallu et al[@421157] |

| Performance Metrics |

Three studies reported common performance metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, AUC-ROC, and convergence rates, noting that federated models generally matched or outperformed local models, particularly where local data was insufficient. |

Albalawi et al[@421156]; Xu et al[@421169] |

| Frameworks |

|

|

| Unit of Federation |

Three studies reported that units of federation included individual hospitals, regional health networks, and international collaborations, showcasing federated learning's versatility in different contexts. |

Kumar et al[@421158]; Antunes et al[@421139]; Lopes et al[@421153] |

| Participating Countries/Regions |

Two studies reported that while some focused on national data, a substantial number involved multi-national collaborations, demonstrating federated learning's role in facilitating global health informatics. |

Lopes et al[@421153]; Xu et al[@421162] |

| Federated Learning Structure and Topology |

Three studies reported implementing a star topology with a central server coordinating model updates, though some explored decentralized and peer-to-peer topologies. |

Brisimi et al[@421152]; McMahan et al[@421143]; Prayitno et al[@421163] |

| Learning Approach |

Three studies reported that iterative learning approaches were predominant, with continuous model updates as new data became available, though one-shot learning was utilized in some requiring a single round of training. |

Prayitno et al[@421163]; Jeon et al[@421147]; Rauniyar et al[@421165] |

| Evaluation Metrics |

Two studies reported that evaluation metrics encompassed model performance, computational efficiency, and privacy preservation, including accuracy, training time, communication overhead, and robustness to data heterogeneity. |

Gadekallu et al[@421157]; Albalawi et al[@421156] |

| Convergence Analysis |

Three studies reported that convergence rates varied, with some achieving rapid convergence and others requiring extensive tuning, reflecting the complexity of real-world healthcare data. |

Antunes et al[@421139]; McMahan et al[@421143]; Brisimi et al[@421152] |

| Solutions for Heterogeneity |

Three studies reported employing techniques such as federated averaging, personalized models, and heterogeneity-aware aggregation methods to address the challenges of data heterogeneity inherent in federated learning. |

Kumar et al[@421158]; Lopes et al[@421153]; Amirahmadi et al[@421141] |

| Federated Learning vs. Local Models |

Three studies reported that federated models outperformed or matched the performance of locally trained models, particularly where local data was insufficient, illustrating federated learning's potential to leverage distributed data for enhanced predictive power. |

Rajkomar et al[@421140]; Xu et al[@421162]; Pollard et al[@421144] |

| Code Availability |

Two studies reported that code availability was limited, indicating a significant opportunity to enhance transparency and reproducibility by sharing codebases more widely. |

Dhiman et al[@421151]; Jeon et al[@421147] |

| Privacy and Security |

|

|

| Privacy Preservation |

Three studies reported that federated learning preserves privacy by keeping patient data localized while only sharing model updates, minimizing data breach risks and ensuring compliance with regulations, making it suitable for sensitive healthcare applications. |

Dhiman et al[@421151]; Antunes et al[@421139]; Kumar et al[@421158] |

| Security Measures |

Three studies reported implementing advanced security measures such as differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, and encryption techniques within federated learning frameworks, enhancing the confidentiality and integrity of patient data. |

Rauniyar et al[@421165]; Antunes et al[@421139]; Prayitno et al[@421163] |

Data

The studies reviewed showcased a wide range in cohort sizes, with sample sizes per site varying from a few hundred records to millions in large national registries. This reflects federated learning’s capability to handle both small-scale and large-scale data aggregation, which is crucial for creating comprehensive datasets that can improve the accuracy and generalizability of health informatics models. Common outcomes analyzed in previously-published studies included disease prevalence, treatment efficacy, patient outcomes, and predictive analytics. These outcomes are essential for improving patient care and operational efficiencies within healthcare systems.

Modeling

The reviewed studies addressed diverse modeling tasks, including disease prediction, patient outcome forecasting, treatment pathway identification, and clinical workflow optimization.1,21,26 Various machine learning models were employed, with three studies reporting the use of models ranging from traditional statistical approaches to advanced neural networks and ensemble methods, focusing on their adaptation to the distributed nature of federated learning.18,26 Hyperparameter optimization methods predominantly included grid search and random search, with two studies14,17 noting these approaches, while some adopted Bayesian optimization for improved efficiency.9 Performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, AUC-ROC, and convergence rates were commonly reported, with three studies providing robust benchmarks for model evaluation.2,6,20 Comparisons between federated models and locally trained models frequently demonstrated superior or equivalent performance for federated models, particularly in scenarios where local data was insufficient for robust model training, highlighting federated learning’s potential to leverage distributed data for enhanced predictive power and model robustness.

Federated Learning Frameworks

Federated learning frameworks varied significantly across the studies, with units of federation including individual hospitals, regional health networks, and international collaborations. This showcases federated learning’s versatility in different contexts. Many studies were nationally focused, but a substantial number involved multi-national collaborations, emphasizing federated learning’s role in facilitating global health informatics.

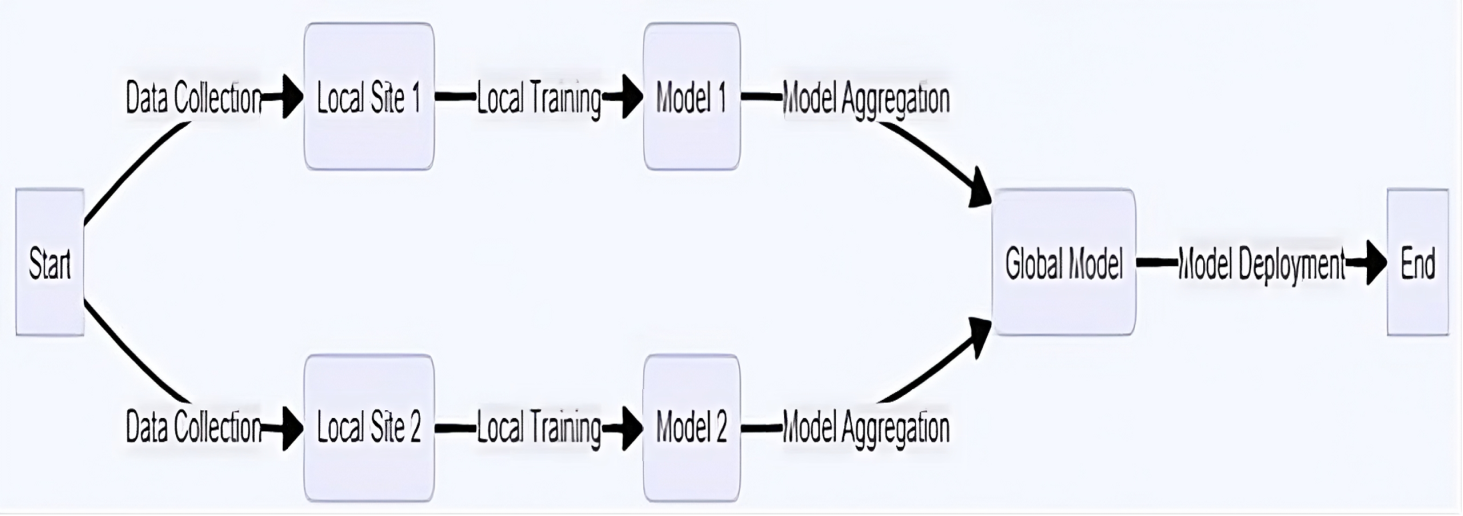

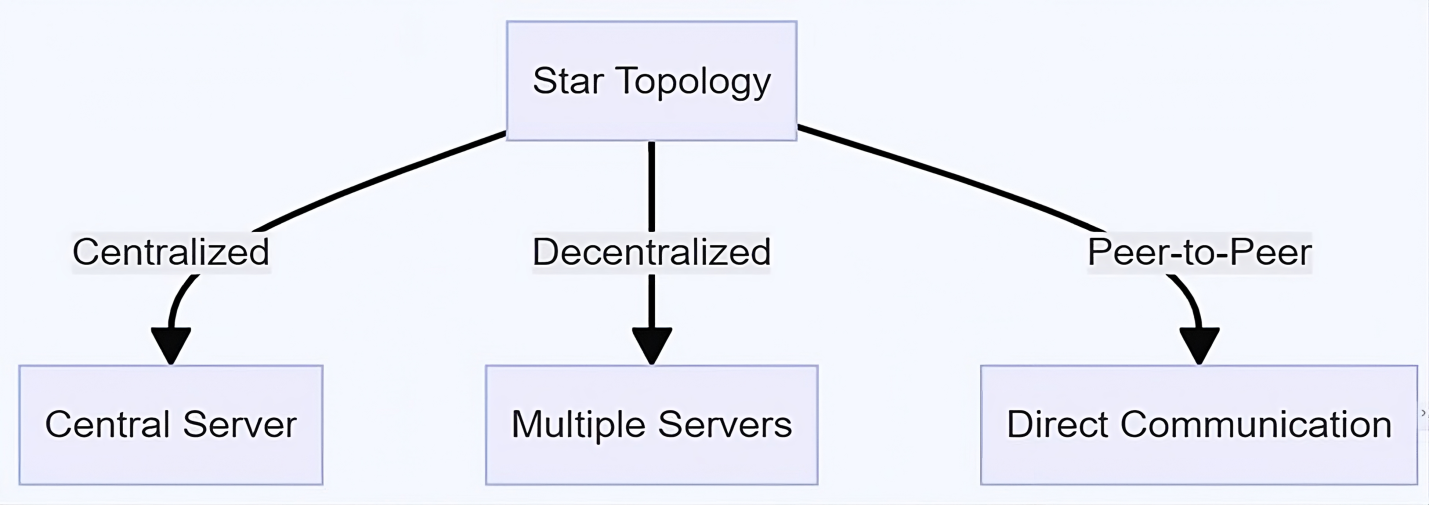

Most federated learning implementations followed a star topology (Figure 3) with a central server coordinating model updates, although decentralized and peer-to-peer topologies were also explored. Iterative learning approaches were predominant, where continuous model updates were made as new data became available. One-shot learning was utilized in specific scenarios requiring a single round of training. The federated learning process in EHR systems, encompassing data localization, model updates, and aggregation, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.PRISMA flow diagram of search for interoperability terminology in electronic health records

Figure 2.Flowchart of the federated learning process in electronic health records systems

Figure 3.Illustration of federated learning framework topologies

Evaluation metrics encompassed model performance, computational efficiency, and privacy preservation, with particular attention to accuracy, training time, communication overhead, and robustness to data heterogeneity. Convergence rates varied, with some studies achieving rapid convergence and others requiring extensive tuning, reflecting the complexity of real-world healthcare data. Techniques such as federated averaging, personalized models, and heterogeneity-aware aggregation were commonly employed to address the challenges of data heterogeneity inherent in federated learning.

Evidence of Heterogeneity

Handling heterogeneous data across sites is a significant challenge for both federated learning and clinical practice. Three reviewed studies emphasized this issue, addressing it through federated averaging, personalized models, and heterogeneity-aware aggregation methods.3,15,19 These approaches allowed federated learning to adapt to diverse data distributions and ensure robust model performance across varied clinical environments. For instance, two studies3,19 developed personalized federated learning frameworks that tailored models to local data characteristics while maintaining a global model’s generalizability.

Federated models consistently outperformed localized models, particularly in multi-institutional studies where local data was limited or fragmented, as reported by three studies: Rajkomar et al,2 Xu et al,20 and Pollard et al6 Federated models showed superior performance in predicting rare diseases, integrating diverse data types, and generalizing across different patient demographics and clinical settings. This comparative advantage, supported by the same research,2,6,20 from underscores the potential of federated learning to improve predictive analytics and patient outcomes, especially in scenarios where data fragmentation is a significant barrier.

Privacy and Security

A core advantage of federated learning is its ability to preserve privacy by keeping patient data localized while only sharing model updates, as highlighted by three studies: Dhiman et al,13 Antunes et al,1 Kumar et al19 This approach minimized the risk of data breaches and ensured compliance with data protection regulations, making federated learning particularly suitable for sensitive healthcare applications. Two studies21,26 reported implementing advanced security measures such as differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, and encryption techniques within federated learning frameworks, further enhancing the confidentiality and integrity of patient data during the federated learning process.

DISCUSSION

The findings presented in this study illuminate the transformative potential of federated learning in the realm of EHR systems, emphasizing its role in fostering standardization and interoperability to advance health informatics. The integration of federated learning into EHR systems promises to revolutionize health informatics by addressing the pressing need for standardization and interoperability. In the United States, where healthcare delivery is often fragmented across numerous providers and systems, achieving seamless data exchange is paramount.16

Data Standardization and Integration

The findings from the reviewed studies shed light on the remarkable versatility of federated learning in effectively handling data across a vast spectrum of cohort sizes, ranging from smaller, localized datasets to expansive national registries.17,25 This innate adaptability underscores federated learning’s capacity to seamlessly aggregate data from diverse sources, irrespective of their scale or geographical distribution, thereby addressing the scalability requirements inherent in modern healthcare systems.

Federated learning’s ability to aggregate data seamlessly from disparate sources not only demonstrates its technical prowess but also signifies its pivotal role in accommodating the diverse needs and complexities of healthcare data management.18 Whether dealing with datasets from individual clinics, regional healthcare networks, or even nationwide registries, federated learning has proven to be a reliable and flexible solution capable of harmonizing data from various sources into a cohesive framework for analysis and decision-making.

Moreover, the utilization of federated learning in analyzing common outcomes such as disease prevalence, treatment efficacy, patient outcomes, and predictive analytics underscores its pivotal role in facilitating a comprehensive and holistic approach to improving healthcare delivery.19 By leveraging the collective intelligence embedded within these diverse datasets, federated learning empowers healthcare stakeholders to glean invaluable insights, identify patterns, and make data-driven decisions that positively impact patient care and operational efficiencies across the healthcare continuum.

Furthermore, the active involvement of multiple sites in the federated learning process, spanning individual healthcare providers to extensive networks encompassing numerous institutions, underscores its inherent capacity to transcend organizational boundaries and foster collaboration across the healthcare landscape.26 This collaborative framework not only promotes the exchange of knowledge and best practices but also fosters a culture of interoperability and standardization within EHR systems, laying the foundation for a more cohesive and integrated healthcare ecosystem.27,28

Within the modeling domain, the results of the reviewed studies provide compelling evidence of the vast scope and versatility of federated learning in addressing an array of healthcare challenges.,20,21,26 These studies showcase federated learnings adeptness in tackling a diverse range of tasks critical to health informatics, including disease prediction, patient outcome forecasting, treatment pathway identification, and clinical workflow optimization.26,29 By delving into such multifaceted areas, federated learning demonstrates its capability to contribute significantly to improving healthcare outcomes and operational efficiencies across various domains within the healthcare landscape.

One of the most striking aspects illuminated by the findings is the breadth of tasks successfully undertaken by federated learning models, as demonstrated in a holistic manner in the research by Liu et al30 and Fauzi et al29 From predicting the onset of diseases to forecasting patient outcomes and optimizing clinical workflows, federated learning emerged as a versatile tool capable of addressing a myriad of healthcare needs. This broad applicability underscores federated learning’s potential to serve as a foundational framework for driving innovation and advancement in health informatics, empowering healthcare practitioners and decision-makers with valuable insights derived from diverse datasets.

Moreover, the utilization of a wide spectrum of machine learning models within the federated learning framework further amplifies its adaptability to different modeling needs and complexities, as highlighted by Peng et al22 Ranging from traditional statistical methods to cutting-edge neural networks and ensemble techniques, federated learning leverages an arsenal of modeling approaches to address the intricacies inherent in healthcare data. This flexibility allows federated learning to tailor its approach to the specific requirements of each modeling task, ensuring optimal performance and accuracy in diverse healthcare scenarios.

The incorporation of comprehensive performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and convergence rates, serves as a testament to the rigor and robustness of federated learning model evaluation.22,31 By employing a standardized set of metrics, researchers can effectively assess the efficacy and performance of federated learning models across various healthcare settings, thereby facilitating meaningful comparisons and informed decision-making. Of particular significance is the compelling evidence indicating that federated learning models consistently outperform or match locally trained models in predictive accuracy and performance metrics.22 This demonstration of federated learning’s superior predictive power underscores its ability to harness the collective intelligence embedded within distributed datasets, thereby leveraging the wealth of information available across multiple healthcare sites to enhance model performance and efficacy. This not only highlights federated learning’s potential to drive advancements in healthcare analytics, but also reaffirms its role as a transformative force in leveraging distributed data for improved patient outcomes and healthcare delivery.

Framework Versatility and Privacy Considerations

The exploration of federated learning frameworks within the reviewed studies uncovers a rich tapestry of implementation strategies, spanning from localized collaborations within individual hospitals to expansive international partnerships.31,32 This diversity underscores federated learning’s remarkable versatility in adapting to the varied contexts and complexities of healthcare environments. Notably, the adoption of iterative learning approaches and the utilization of a diverse array of evaluation metrics reflect a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted considerations essential to successful federated learning implementation.

From prioritizing computational efficiency and model performance to ensuring stringent privacy preservation measures, these strategies underscore a holistic approach aimed at optimizing federated learning’s efficacy within healthcare settings.33 Furthermore, the integration of advanced techniques such as federated averaging, personalized models, and heterogeneity-aware aggregation methods underscores a concerted effort to surmount the challenges posed by data heterogeneity inherent in federated learning environments.34 By embracing these innovative approaches, researchers demonstrate a commitment to harnessing the full potential of federated learning while mitigating the complexities associated with disparate data distributions across participating sites.

Moreover, the emphasis on transparency and reproducibility through the availability of code and methodologies underscores a commitment to fostering collaboration and upholding research integrity within the realm of healthcare informatics.32,33 By promoting open access to tools and methodologies, researchers aim to facilitate knowledge sharing, enhance collaboration, and accelerate advancements in federated learning-driven healthcare analytics.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings underscore that federated learning significantly enhances the ability to standardize and interoperate EHR systems by facilitating secure and efficient health data sharing and analysis across diverse healthcare settings. Key insights from the literature review revealed that federated learning models consistently outperformed or match localized models, particularly in scenarios where local data was limited or fragmented. This comparative advantage is especially pronounced in predicting rare diseases, integrating diverse data types, and generalizing across different patient demographics and clinical settings.

A critical challenge identified is the handling of heterogeneous data across sites, which is adeptly managed by federated learning through techniques such as federated averaging, personalized models, and heterogeneity-aware aggregation methods. These methods ensure robust model performance and adaptability across varied clinical environments. Moreover, federated learning’s core advantage in preserving privacy and security by keeping patient data localized and only sharing model updates is well-supported by the literature. Advanced security measures like differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, and encryption techniques further enhance data confidentiality and integrity.

Despite these significant benefits of federated learning, our review also highlighted areas for improvement, such as the need for more open data initiatives and increased code availability to enhance transparency and reproducibility in federated learning research. Addressing these gaps will be crucial for realizing the full potential of federated learning in healthcare.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have nothing to disclose.

FUNDING

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Bibliography

-

1.

Antunes RS, Da Costa CA, Küderle A, Yari IA, Eskofier BM. Federated Learning for Healthcare: Systematic Review and Architecture Proposal.

ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 2022;13(4):1-23. doi:

10.1145/3501813

-

2.

Rajkomar A, Oren E, Chen K, et al. Scalable and Accurate Deep Learning with Electronic Health Records.

NPJ Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):18. doi:

10.1038/s41746-018-0029-1

-

3.

Amirahmadi A, Ohlsson M, Etminani K. Deep Learning Prediction Models Based on EHR Trajectories: A Systematic Review.

Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2023;104(430):104430. doi:

10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104430

-

4.

Deng R, Long Z, Peng L, Kuang D, et al. A New Mathematical Expression for the Relation Between Characteristic Temperature and Glass-Forming Ability of Metallic Glasses.

Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 2020;533:119829. doi:

10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2019.119829

-

5.

McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, Aguera y Arcas B. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In: Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR; 2017:1273-1282.

-

6.

Pollard TJ, Johnson AEW, Raffa JD, Celi LA, Mark RG, Badawi O. The eICU Collaborative Research Database: A Freely Available Multi-Center Database for Critical Care Research.

Scientific Data. 2018;5(1):1-13. doi:

10.1038/sdata.2018.178

-

7.

Patel V et al. Adoption of Federated Learning for Healthcare Informatics: Emerging Applications and Future Directions.

IEEE Access. 2022;10:90792-90826. doi:

10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3201876

-

8.

Zeydan E, Arslan S, Liyanage M. Managing Distributed Machine Learning Lifecycle for Healthcare Data in the Cloud.

IEEE Access. 2024;12:115750-115774. doi:

10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3443520

-

9.

Jeon K et al. Advancing Medical Imaging Research Through Standardization: The Path to Rapid Development, Rigorous Validation, and Robust Reproducibility.

Investigative Radiology. doi:

10.1097/RLI.0000000000001106

-

10.

Wang F, Preininger A. AI in Health: State of the Art, Challenges, and Future Directions.

Yearbook of Medical Informatics. 2019;28:16-26. doi:

10.1055/s-0039-1677908

-

11.

Majeed IA, Min HK, Tadi VSK, et al. Factors Influencing Cost and Performance of Federated and Centralized Machine Learning. In:

2022 IEEE 19th India Council International Conference (INDICON). IEEE; 2022:1-6. doi:

10.1109/INDICON56171.2022.10040166

-

12.

Hur K, Oh J, Kim J, et al. GenHPF: General Healthcare Predictive Framework for Multi-Task Multi-Source Learning.

IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. Published online 2023. doi:

10.1109/JBHI.2023.3327951

-

13.

Dhiman G, Juneja S, Mohafez H, El-Bayoumy I, Sharma LK, Hadizadeh M, et al. Federated Learning Approach to Protect Healthcare Data over Big Data Scenario.

Sustainability. 2022;14(5):2500. doi:

10.3390/su14052500

-

14.

Brisimi TS, Chen R, Mela T, Olshevsky A, Paschalidis IC, Shi W. Federated Learning of Predictive Models from Federated Electronic Health Records.

International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2018;112:59-67. doi:

10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.01.007

-

15.

Lopes RR, Mamprin M, Zelis JM, et al. Local and Distributed Machine Learning for Inter-Hospital Data Utilization: An Application for TAVI Outcome Prediction.

Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2021;8. doi:

10.3389/fcvm.2021.787246

-

16.

Hwang SO, Majeed A. Analysis of Federated Learning Paradigm in Medical Domain: Taking COVID-19 as an Application Use Case.

Applied Sciences. 2024;14(10):4100. doi:

10.3390/app14104100

-

17.

Albalawi E, TR M, Thakur A, et al. Integrated Approach of Federated Learning with Transfer Learning for Classification and Diagnosis of Brain Tumor.

BMC Medical Imaging. 2024;24(1). doi:

10.1186/s12880-024-01261-0

-

18.

Gadekallu TR, Pham Q, Huynh-The T, Bhattacharya S, Maddikunta PKR, Liyanage M. Federated Learning for Big Data: A Survey on Opportunities, Applications, and Future Directions.

arXiv.org.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.04160

-

19.

Kumar Y, Singla R. Federated Learning Systems for Healthcare: Perspective and Recent Progress. In:

Studies in Computational Intelligence. ; 2021:141-156. doi:

10.1007/978-3-030-70604-3_6

-

20.

Xu J, Glicksberg BS, Su C, Walker P, Bian J, Wang F. Federated Learning for Healthcare Informatics.

Journal of Healthcare Informatics Research. 2020;5(1):1-19. doi:

10.1007/s41666-020-00082-4

-

21.

Prayitno KT, Shyu H, Putra Y, Hossain KSMT, Jiang W, Shae Z. A Systematic Review of Federated Learning in the Healthcare Area: From the Perspective of Data Properties and Applications.

Applied Sciences. 2021;11(23):11191. doi:

10.3390/app112311191

-

22.

Peng L, Luo G, Walker A, et al. Evaluation of Federated Learning Variations for COVID-19 Diagnosis Using Chest Radiographs from 42 US and European Hospitals.

Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2022;30(1):54-63. doi:

10.1093/jamia/ocac188

-

-

24.

Rauniyar A, Hagos DH, Jha D, et al. Federated Learning for Medical Applications: A Taxonomy, Current Trends, Challenges, and Future Research Directions.

IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2024;11(5):7374-7398. doi:

10.1109/JIOT.2023.3329061

-

25.

Fathima AS, Basha SM, Ahmed ST, et al. Federated Learning-Based Futuristic Biomedical Big-Data Analysis and Standardization.

PLOS ONE. 2023;18(10):e0291631. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0291631

-

26.

Ghadi YY, Mazhar T, Shah SFA, et al. Integration of Federated Learning with IoT for Smart Cities Applications, Challenges, and Solutions.

PeerJ Computer Science. 2023;9:e1657. doi:

10.7717/peerj-cs.1657

-

27.

Haidar A, Mouiee DA, Aly F, Thwaites D, Holloway L. Exploring Federated Deep Learning for Standardising Naming Conventions in Radiotherapy Data.

arXiv. Published online 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.08999

-

28.

Morafah M, Reisser M, Lin B, Louizos C. Stable Diffusion-Based Data Augmentation for Federated Learning with Non-IID Data.

arXiv. Published online 2024.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.07925

-

29.

Fauzi MA, Yang B, Blobel B. Comparative Analysis Between Individual, Centralized, and Federated Learning for Smartwatch-Based Stress Detection.

Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022;12(10):1584. doi:

10.3390/jpm12101584

-

30.

Liu B, Lv N, Guo Y, Li Y. Recent Advances on Federated Learning: A Systematic Survey.

arXiv. Published online 2023. doi:

10.48550/arxiv.2301.01299

-

-

32.

Nevrataki T, Iliadou A, Ntolkeras G, et al. A Survey on Federated Learning Applications in Healthcare, Finance, and Data Privacy/Data Security.

AIP Conference Proceedings. Published online 2023. doi:

10.1063/5.0182160

-

-

34.

Li L, Fan Y, Tse M, Lin K. A Review of Applications in Federated Learning.

Computers & Industrial Engineering. 2020;149:106854. doi:

10.1016/j.cie.2020.106854